Why Was Paris's Cabaret of Hell So Sinister? Inside the Belle Époque's Infamous Cabaret du Néant

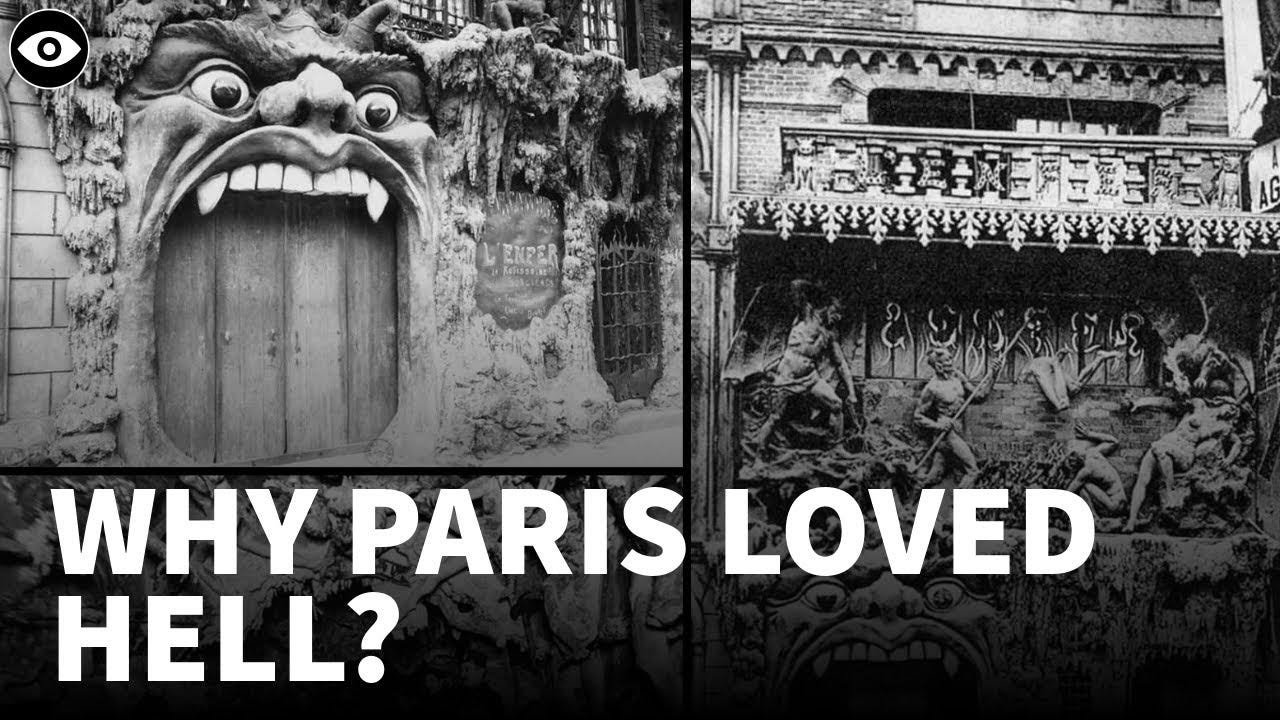

Paris during the Belle Époque (roughly 1871-1914) evokes images of vibrant artistic expression, burgeoning modernity, and exuberant joie de vivre. The Moulin Rouge kicked its legs high, Impressionists captured fleeting moments of light, and the Eiffel Tower pierced the skyline as a symbol of progress. Yet, beneath this glittering surface, a parallel current of fascination with the morbid, the decadent, and the transgressive pulsed through the city. Nowhere was this darker fascination more commercially and theatrically realised than in the infamous cabarets of Montmartre, particularly the chillingly named Cabaret du Néant (Cabaret of Nothingness) and its fiery neighbour, the Cabaret de l'Enfer (Cabaret of Hell). While L'Enfer offered a cartoonish, fire-and-brimstone vision of damnation, it was arguably the Cabaret du Néant, with its stark confrontation with mortality and oblivion, that possessed a deeper, more unsettling sinister quality. What made these establishments, especially the Néant, feel so profoundly disturbing to contemporaries and so fascinating to us now?

Montmartre's Macabre Triangle: Setting the Stage

Montmartre in the late 19th century was the epicenter of Parisian bohemian life. Artists, writers, performers, and thrill-seekers flocked to its slopes, drawn by cheap rents and an atmosphere of creative freedom and moral ambiguity. Amidst the traditional cafés and dance halls, a new breed of themed entertainment emerged – the *cabaret artistique*. These venues offered more than just drinks and songs; they provided immersive, often provocative experiences. On the Boulevard de Clichy, near the Place Pigalle, a particularly notorious cluster emerged: the Cabaret de l'Enfer, the Cabaret du Néant, and, for a time, the ironically juxtaposed Cabaret du Ciel (Cabaret of Heaven). This trifecta represented a stark, commercialised journey through the afterlife, playing directly on the era's anxieties and curiosities about death, salvation, and the void.

The very existence of these establishments speaks volumes about the fin-de-siècle mindset. It was an era caught between lingering religious traditions and the rise of scientific rationalism, industrialisation, and new psychological theories. Death, while always a human preoccupation, took on a particular resonance. Advances in medicine paradoxically highlighted the fragility of life, while secularisation left a vacuum where religious assurances about the afterlife once stood. These cabarets, therefore, weren't just entertainment; they were commercialised explorations of existential dread and societal taboos.

Inside the Cabaret de l'Enfer: A Devilishly Good Time?

The Cabaret de l'Enfer was perhaps the more overtly theatrical of the pair. Its facade was a spectacle in itself – a gaping hell-mouth, often sculpted with demonic figures, beckoning patrons into its infernal depths. Inside, the theme continued relentlessly. Dim, reddish lighting cast eerie shadows, plaster demons leered from the walls, and waiters dressed as devils served drinks with names like "Styx water" or perhaps something evoking brimstone. The atmosphere was deliberately chaotic and unsettling, often featuring discordant music, performers reciting damned poetry, or satirical skits mocking religious figures and concepts of eternal punishment. It was a Bosch painting brought to life, albeit with a wink and a nod to its own absurdity. While startling and perhaps blasphemous to some, its horror was largely performative, a kind of Grand Guignol theatre of damnation. It played on familiar tropes of hell, making the fear recognisable, almost comfortable in its familiarity.

The Cabaret du Néant: Staring into the Abyss

Adjacent to the boisterous hellfire of L'Enfer stood the Cabaret du Néant, offering a profoundly different, and arguably more disturbing, experience. Its theme wasn't eternal torment, but absolute annihilation. The entrance often resembled a mausoleum or crypt. Patrons entered a space deliberately designed to evoke a funeral parlour or burial vault. The decor featured skulls, bones, and funereal drapery. Instead of tables, guests often sat around coffins. Drinks, sometimes morbidly named "bières de la mort" (beers of death), were served in skull-shaped mugs or laboratory beakers by waiters dressed as pallid undertakers or monks.

The entertainment matched the decor. Morbid poems were recited, dirges were sung, and the general atmosphere was one of hushed, chilling contemplation of mortality. The centerpiece, however, was a technological marvel of the time used to deeply unsettling effect: an illusion based on the principle of Pepper's Ghost. A volunteer patron would be invited into a coffin-like structure. Through clever use of lighting and angled glass panes (the Pepper's Ghost technique), the audience would watch as the person's reflection appeared to gradually decompose, their flesh fading away to reveal a grinning skeleton, before dissolving into nothingness. This wasn't about devils and pitchforks; it was about the stark, scientific, and terrifying reality of decay and oblivion.

"The Néant did not merely simulate hell; it simulated the terrifying prospect that after death, there was simply... nothing. No heaven, no hell, just the cold, silent void. In an age grappling with secularism, this was perhaps the ultimate horror."

The Root of the Sinister: Beyond Decor and Illusions

So, why did the Cabaret du Néant, in particular, feel so sinister? The answer lies beyond the spooky props and clever illusions. Its power stemmed from its direct confrontation with the deepest existential anxieties of the Belle Époque, anxieties that still resonate today.

Firstly, it commodified the ultimate taboo. Death, grief, and the fear of non-existence were transformed into a night out, a consumable experience. This trivialisation of the profound, turning existential dread into entertainment, could itself feel deeply unsettling, even perverse. It suggested a society losing its reverence, perhaps its very anchor, in the face of mortality.

Secondly, the Néant tapped into the burgeoning fear of meaninglessness fostered by scientific materialism and declining religious faith. While Hell, however terrifying, offered a form of continuity and cosmic justice, the Néant presented the stark alternative: complete erasure. The Pepper's Ghost illusion wasn't just a magic trick; it was a visual metaphor for the annihilation of the self, the reduction of life to mere decaying matter. This prospect of utter void, of non-being, is arguably a more profound and modern horror than traditional images of damnation.

Thirdly, the experience was deeply psychological. Unlike the more externalised spectacle of L'Enfer, the Néant forced introspection. Sitting in a coffin, drinking from a skull, watching a simulated decomposition – these acts prompted patrons to contemplate their own mortality in a direct, visceral way. It blurred the line between observer and participant in the macabre theatre of death.

The juxtaposition with L'Enfer and Le Ciel further heightened the effect. Patrons could literally walk from a kitschy Heaven, through a fiery Hell, into the cold embrace of Nothingness, all within the same evening on the Boulevard de Clichy. This created a disturbing equivalence, suggesting these ultimate destinations were merely different flavours of entertainment, robbing them of their traditional weight and significance.

Explore the unsettling atmosphere captured in contemporary footage and artistic interpretations:

The sinister nature of the Cabaret du Néant wasn't just about skeletons and coffins; it was about the cold reflection it offered of a society grappling with rapid change, questioning old certainties, and staring into the newly perceived abyss of a godless, meaningless universe. It weaponised the era's existential anxieties and sold them back as entertainment.

Legacy of the Macabre Cabarets

The Cabaret du Néant and the Cabaret de l'Enfer eventually faded, victims of changing tastes, the horrors of World War I which made theatrical death seem trivial, and the relentless march of urban development. Yet, their legacy lingers. They represent a fascinating chapter in the history of entertainment, popular culture, and the public expression of private fears. They prefigured aspects of modern horror entertainment, theme parks (think haunted houses), and our enduring cultural fascination with death and the macabre. They stand as monuments to a specific historical moment when the anxieties of modernity found expression in the most bizarre and theatrical of forms.

These cabarets remind us that the veneer of progress and sophistication often hides deeper, unresolved fears. The Belle Époque, despite its name, was not immune to darkness. The success of the Cabaret du Néant reveals a profound societal unease, a willingness – even a need – to confront the void, even if only through the mediated experience of a themed bar.

The Cabaret du Néant wasn't merely sinister because it depicted death; it was sinister because it dared to depict nothingness, holding up a mirror to the modern soul's deepest fear: the possibility that beneath the vibrant dance of life lies only the cold, silent, and inescapable void.