THE WAGES OF WHITENESS

The Systematic Sabotage of the American Proletariat

History is often written as a sequence of inevitabilities, but the archival record reveals ghost roads—paths not taken that terrified the ruling class. We begin with a visual anomaly in the American labor narrative: a moment when the racial caste system briefly buckled under the weight of class consciousness.

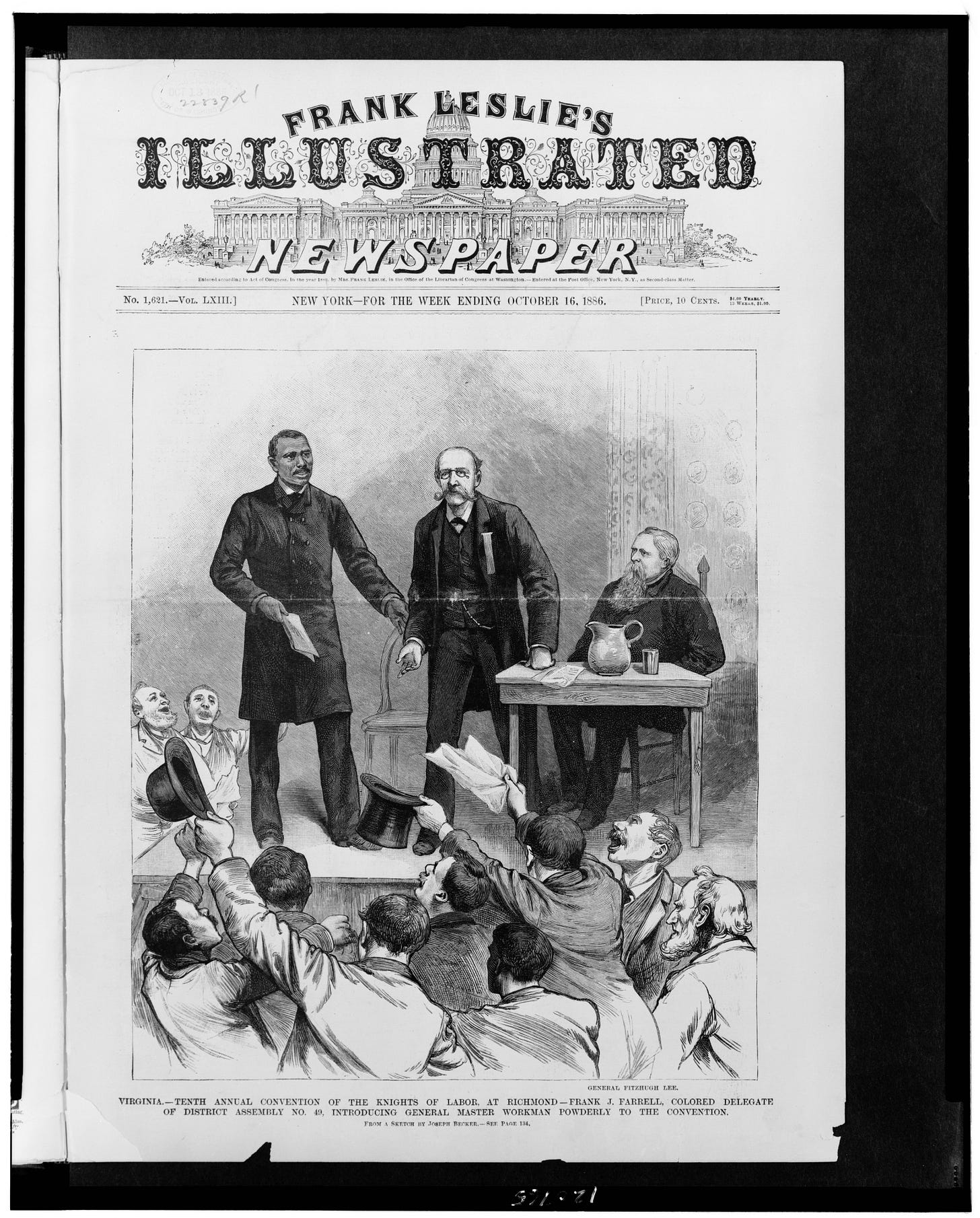

This woodcut from *Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper* (1886) documents the Tenth Annual Convention of the Knights of Labor in Richmond, Virginia. The visual center of gravity is not merely General Master Workman Terence Powderly, but the man introducing him: Frank J. Farrell, a Black delegate from District Assembly No. 49. This image captures the precise moment the American aristocracy held its breath. The Knights of Labor, unlike the trade unions that would follow, organized across lines of skill, gender, and, crucially, race. They recognized that a divided working class was a conquered working class. Here, Farrell is not a subordinate; he is a bridge. He represents a terrifying possibility to Southern planters and Northern industrialists alike: that the white mechanic and the Black field hand might recognize they shared a common enemy.

THE PRESENCE OF A BLACK MAN ON A PODIUM IN THE FORMER CAPITAL OF THE CONFEDERACY WAS NOT PROGRESS; IT WAS AN EXISTENTIAL THREAT TO THE POST-WAR ECONOMIC ORDER.

However, the visual optimism here is deceptive. While the Knights advocated for solidarity, the social fabric outside this hall was already being re-stitched with the thread of Jim Crow. The destruction of this solidarity did not happen by accident; it was an engineered demolition. The ruling class quickly realized that to break labor, they did not need to kill the workers; they simply needed to remind the white worker that, no matter how poor, he was still white. This woodcut is a tombstone for a future that was strangled in the crib.

II. The Paper Shackles: Bureaucracy as Bondage

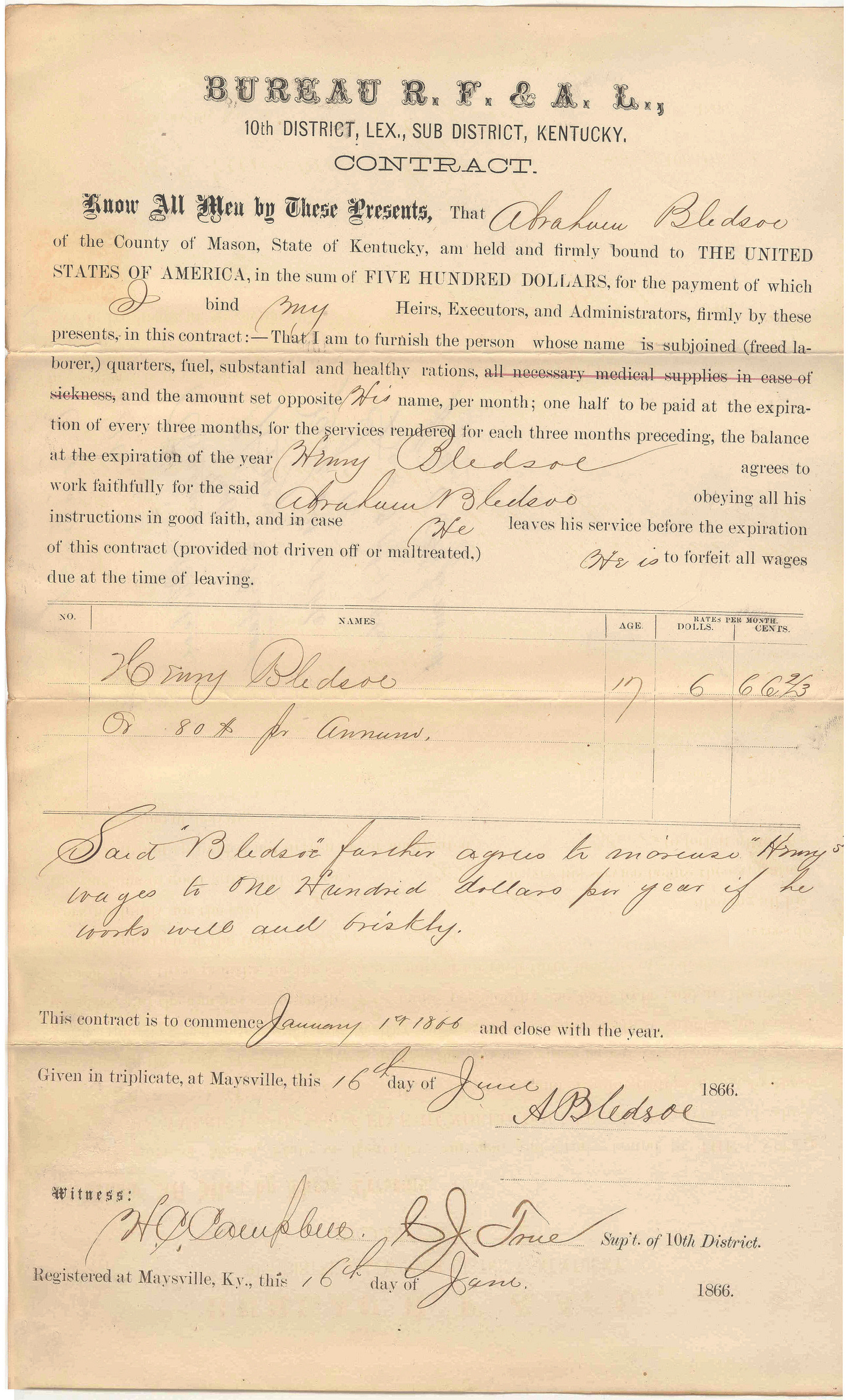

To understand how the solidarity of the Knights was dismantled, we must look at the legal infrastructure built to contain Black labor immediately following the Civil War. Emancipation effectively destroyed $3 billion in capital investments (enslaved human beings), and the Southern economy required a mechanism to replace that lost capital without paying market wages.

This document, a contract from the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (the Freedmen’s Bureau), exposes the bureaucratic transition from chattel slavery to debt peonage. The contract binds “Harry” (no surname recorded, stripping him of full personhood even in freedom) to Abraham Bledsoe. The terms are not a negotiation between free agents; they are a dictation of terms by the state on behalf of the landowner. Note the chilling boilerplate language: the laborer is bound for a year, risking total forfeiture of wages for “disobedience” or “sickness.” This is the visual evidence of the state stepping in to regulate Black labor for the benefit of white capital.