THE MERCHANDISING OF THE CROSS

Bonhoeffer, American Idolatry, and the High Price of Cheap Grace

We begin not with a politician, but with a prophet. The cover of Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s The Cost of Discipleship

Serves as the primary artifact of our theological baseline. Published in 1937 as *Nachfolge*, this was not merely a devotional text; it was an act of ecclesiastical warfare against a German church that had become comfortable, culturally assimilated, and morally bankrupt. When we gaze upon this title, we are looking at the antidote to the poison spreading through modern Christendom. Bonhoeffer did not write this to comfort the weary; he wrote it to wake the dead.

The tragedy of modern Christianity is that it has taken the cross—an instrument of Roman torture and divine execution—and turned it into a decorative garnish for the status quo. Bonhoeffer’s central thesis defines ‘Cheap Grace’ as the deadly enemy of the church. It is the preaching of forgiveness without requiring repentance, baptism without church discipline, communion without confession. It is grace without discipleship, grace without the cross, grace without Jesus Christ, living and incarnate. In the visual simplicity of this book cover, there is a stark rejection of the consumerist religion that would follow decades later.

CHEAP GRACE IS THE JUSTIFICATION OF SIN WITHOUT THE JUSTIFICATION OF THE REPENTANT SINNER. IT IS THE GRACE WE BESTOW ON OURSELVES.

This text establishes the rubric by which we must judge every subsequent image in this dossier. Bonhoeffer argued that when grace is sold as a bargain-basement commodity, the church ceases to be the body of Christ and becomes a social club for the religious justification of secular power. The ‘cost’ mentioned in the title is absolute—it demands the surrender of one’s life. As we pivot to the artifacts of our current moment, we must ask: Where is the cost? Where is the discipleship? Or are we simply witnessing the sale of indulgences wrapped in the flag?

The Syncretic Artifact: The Heresy of the Hybrid Bible

If Bonhoeffer’s text is the standard, this artifact

Is the deviation. Here we witness the ‘God Bless the USA’ Bible, open to a page that seamlessly transitions from Holy Scripture to the Bill of Rights. Visually, this is a stunning admission of syncretism—the blending of two distinct religious systems into a new, bastardized faith. The layout itself is the heresy. By placing the founding documents of a nation-state within the same binding and potentially the same font hierarchy as the Word of God, the designers have visually elevated the temporal laws of men to the level of divine revelation.

This is not patriotism; it is idolatry in leather binding. In this image, we see the literal manifestation of the German Christian (Deutsche Christen) error of the 1930s, which sought to harmonize the Volk with the Gospel. The visual proximity of these texts suggests that to be a good American is synonymous with being a faithful Christian, and vice versa—a lie that Bonhoeffer fought against with every fiber of his being. The lighting in the photograph highlights the text of the ‘Bill of Rights,’ casting it in the reverent glow usually reserved for the Psalms.

WHEN THE CONSTITUTION IS ELEVATED TO CANON, THE KINGDOM OF GOD IS DEMOTED TO A POLITICAL PARTY.

Who is not visible here? Christ. The text of the First Amendment is visible, protecting the freedom of religion, but the text of the Beatitudes, which outlines the *practice* of that religion, is nowhere to be seen in this frame. This artifact represents the ultimate triumph of ‘Cheap Grace’: a religion that requires no sacrifice of national identity, no critique of state power, and no allegiance higher than the flag. It offers a Savior who died to ensure your right to bear arms, rather than one who died to reconcile the world to himself.

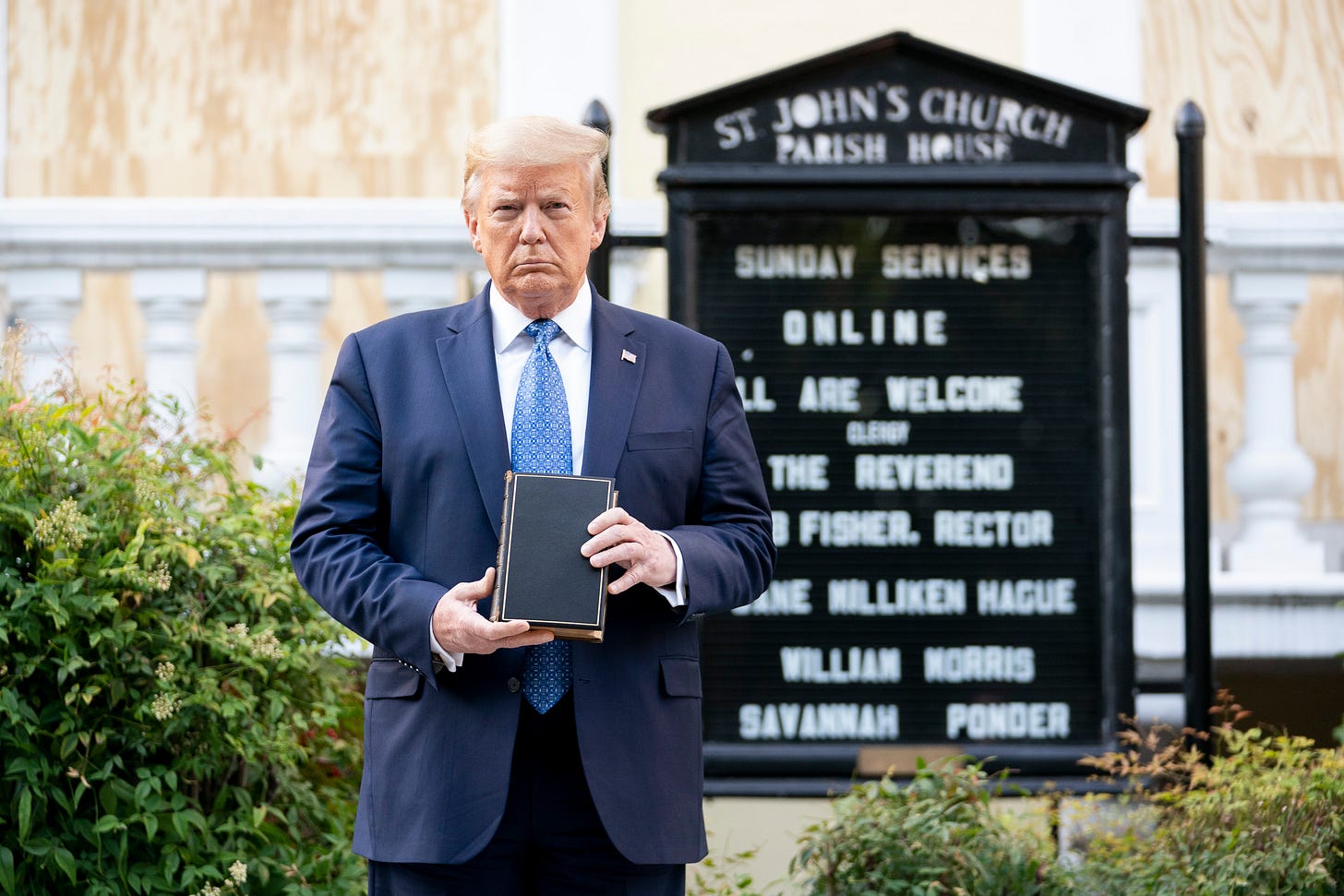

The Totem of State Power: Symbol Over Substance

Captures one of the most defining images of the 21st-century intersection between faith and state. The subject stands in front of St. John’s Church, a historic house of worship that has been boarded up—literally closed off—serving now only as a backdrop for a photo opportunity. The holding of the Bible is the critical visual element here. Note the grip: it is not held as a text to be read, but as a weapon to be brandished. It is closed. There is no finger marking a verse; there is no engagement with the content.

The Bible in this image is not a source of moral instruction; it is a prop of political legitimacy. This is the operational definition of Cheap Grace in the political sphere: claiming the authority of the divine without submitting to the ethics of the divine. The subject uses the symbol of the church to validate secular force—moments before this photo was taken, peaceful protesters were forcibly cleared from the square. Bonhoeffer wrote that the church effectively ceases to exist when it becomes a function of the state. Here, the church is literally boarded up, a hollow shell used to frame a political narrative.

A CLOSED BIBLE HELD UP BY A MAN WHO DOES NOT READ IT IS MORE DANGEROUS THAN AN OPEN BIBLE IN THE HANDS OF AN ATHEIST.

The visual narrative here is transactional. The image says: ‘I protect the symbol, and the symbol protects me.’ It is the exact inverse of the ‘suffering servant’ model of leadership found in the gospels. This is the ‘deadly enemy’ Bonhoeffer warned of—a Christianity that has been stripped of its ethical demands and reduced to a cultural signifier for power and heritage. The board covering the church sign behind him might as well be a tombstone for the separation of church and state.

The Banality of Complicity: Life Under the Shadow

To understand how a society arrives at the point of weaponizing its faith, we must look to the past.

Presents a mundane street scene from the era of the Third Reich. We see a tram, people rushing to work, the blur of daily life. There are no swastikas visible in this specific frame, no marching soldiers, only the gray reality of existence. This image illustrates the environment in which the ‘German Christian’ movement took root. It was not always a dramatic takeover; it was a slow drift of ordinary people who wanted their religion to align with their national resurgence.

Evil does not always arrive with thunder; often, it arrives with the morning commute. These citizens, likely baptized, likely church-goers, were the target audience for the syncretism that Bonhoeffer opposed. They were the ones who found comfort in a church that affirmed their national identity rather than challenging their moral apathy. The blur in the photo suggests movement, a society rushing forward, too busy to notice the ground shifting beneath them.

THE CHURCH DID NOT FALL BECAUSE OF THE VILLAINS; IT FELL BECAUSE OF THE BYSTANDERS.

Bonhoeffer’s struggle was not just against the state, but against this very normalcy—the idea that one could be a ‘good German’ and a Christian while the state dismantled the ethical framework of the faith. This image serves as a mirror to our own time. It asks us: In our rush to maintain our way of life, what compromises are we making? When the Bible is merged with the Constitution, or held as a prop, do we stop the tram? Or do we just keep commuting, grateful for the Cheap Grace that allows us to ignore the cost?

The Final Calculation: Costly Grace

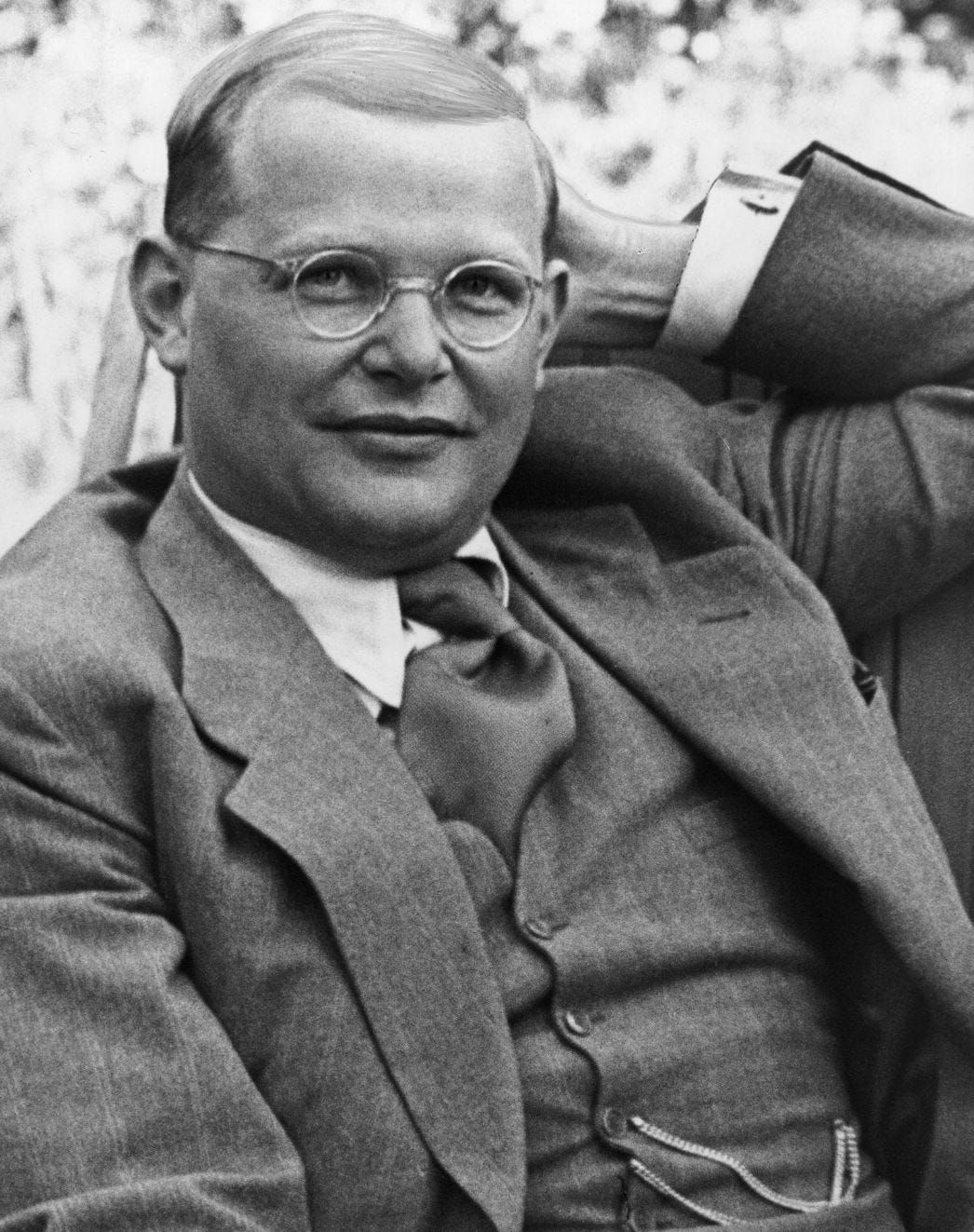

Finally, we confront the man himself.

Shows Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the theologian who lived the antithesis of the images we have just analyzed. His gaze is direct, his expression contemplative but unyielding. This is a man who had every opportunity to escape. He was safely in New York in 1939; he could have stayed in the academic luxury of Union Theological Seminary. Instead, he took the last ship back to Germany before the war started, writing that he could not participate in the reconstruction of Christian life in Germany after the war if he did not share in the trials of this time with his people.

This is what Costly Grace looks like: a suit worn by a man destined for a prison uniform. There is no prop here. There is no flag. There is only a human being who understood that the call to follow Christ is a call to come and die. While the modern artifacts of

and

seek to preserve power and safety, Bonhoeffer’s life was a deliberate expenditure of both.

WE HAVE GATHERED LIKE VULTURES AROUND THE CARCASS OF CHEAP GRACE, AND THERE WE HAVE DRUNK THE POISON WHICH HAS KILLED THE LIFE OF FOLLOWING CHRIST.

In the end, the contrast is devastating. We have on one side a Christianity that is printed on bonded leather next to the Bill of Rights, safe, proud, and nationalistic. On the other, we have a faith that led a pacifist theologian to the gallows at Flossenbürg concentration camp. The ‘God Bless the USA’ Bible costs $59.99. The discipleship Bonhoeffer wrote about costs everything. As we look at his face, we must ask ourselves which version of the faith we have subscribed to: the one that guarantees our rights, or the one that demands our lives?