The Digital Demesne: Vertical Integration as Neo-Feudalism

The medieval manor was not merely a farm; it was a total institution designed to maximize extraction through the illusion of safety. This investigation argues that the modern ‘Walled Garden’ tech ecosystem is a direct historical successor to manorialism, where user convenience is traded for a total loss of digital sovereignty. We analyze the specific mechanisms of lock-in—from the ‘Blue Bubble’ social capital to the 30% app store tithe—to reveal that we have not evolved past serfdom; we have merely digitized the soil.

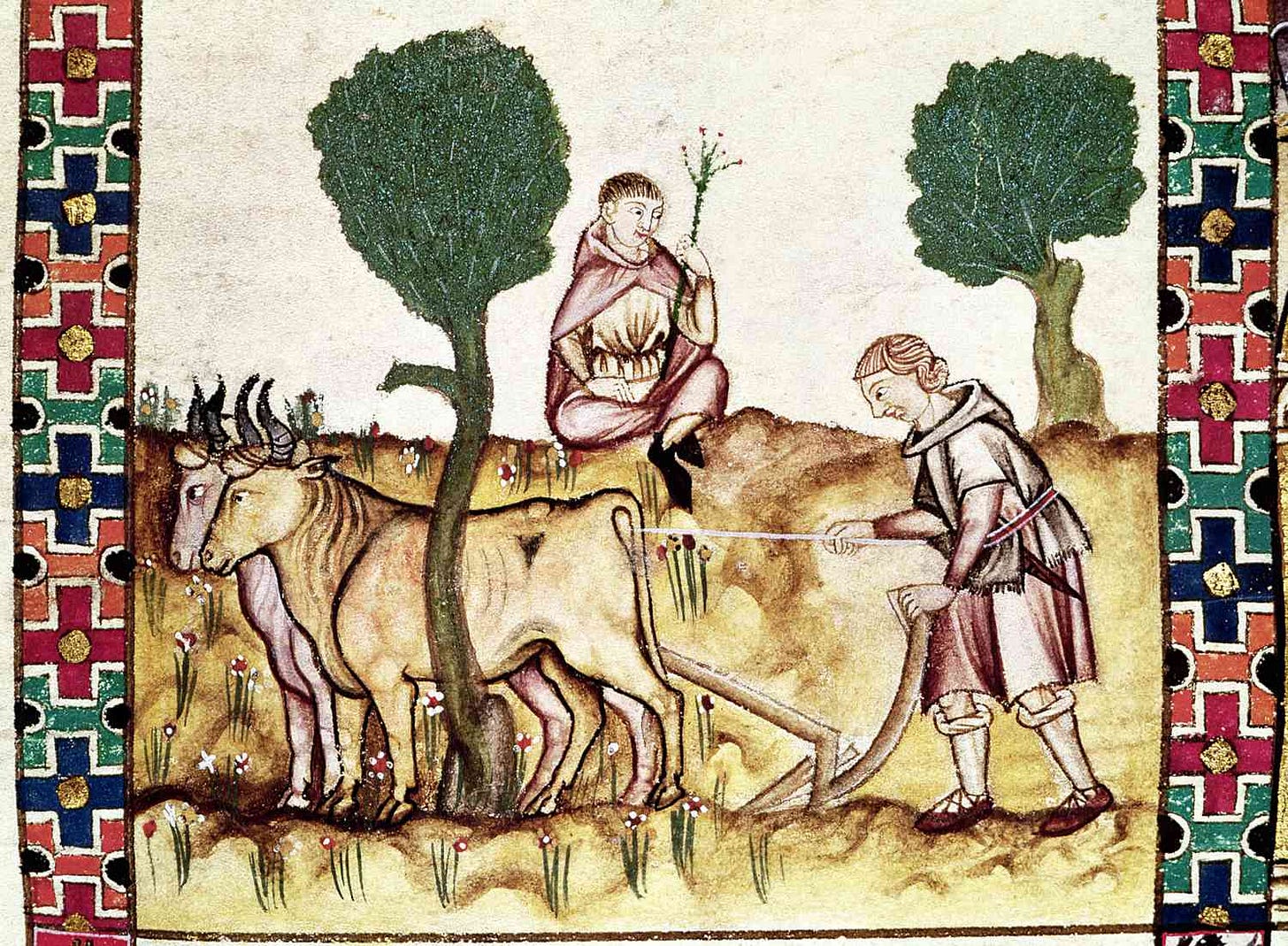

Freedom, in the agrarian age, was defined not by what you owned, but by your ability to leave. The serf was distinct from the slave in one crucial legal aspect: the slave was property to be bought and sold, but the serf was *adscripticius glebae*—bound to the soil. The serf could not be sold away from the land, but neither could the land be left by the serf. The dirt under his fingernails was the source of his sustenance and the chain around his neck. Look closely at the illuminated manuscript provided. The plowman is not merely working; he is engaged in the maintenance of a closed loop. The oxen, the plow, and the furrow represent the ‘User Experience’ of the 12th century. It is reliable, it is structured, and it is inescapable.

In our digital epoch, the concept of the ‘ecosystem’ is a sanitizing metaphor for this exact form of bondage. When a user purchases a device, they believe they are acquiring a tool. In reality, they are stepping onto the demesne. The hardware is merely the plow; the operating system is the soil. The moment you migrate your data, contacts, and photos into a proprietary cloud, you have become bound to the digital soil. To leave is not merely to switch brands; it is to abandon the harvest of a lifetime. The friction of export, the incompatibility of file formats, and the loss of metadata are the modern equivalents of the feudal law that forbade the peasant from taking his grain off the lord’s land.

The genius of the modern manor is that the walls are painted to look like infinite horizons. We mistake the lack of friction within the system for freedom, when it is actually the lubricant of entrapment.

The plowman in the image does not look up. He is focused on the furrow. This is the posture of the modern user, head down in the feed, plowing the algorithmic field to generate data for a silo they cannot access. The efficiency of the tool—the seamlessness of the plow cutting the earth—is the very mechanism that keeps the head down. If the plow were broken, the serf might look at the horizon. Vertical integration is the perfection of the plow to ensure the serf never contemplates the forest.

The Man Under the Tree: The Passive Rentier

Seated comfortably on the knoll, observing the labor but not participating in it, is the archetype of the Rentier. In the medieval context, this figure represents the Manorial Lord or his Steward. He does not till. He does not sow. He owns the infrastructure of existence. He provides the ‘protection’—the military might to repel bandits and the legal framework to settle disputes. In exchange, he extracts a portion of everything produced on the land. This is not a transaction; it is a structural reality. The peasant cannot shop around for a different lord with lower tax rates because the cost of travel is death or destitution.

The 30% App Store fee is not a commission; it is a feudal quitrent charged for the privilege of existing within the walls.

Consider the optics of the seated figure. He holds a sprig, a symbol of leisure and the natural order. He is naturalizing his dominance. Today, the platform holders argue that their ‘tax’ is necessary to fund the safety of the ecosystem. They claim to curate the App Store to protect the user from ‘malware’—the digital equivalent of protecting the serf from wolves. This is the oldest protection racket in history. The Lord creates a terrifying narrative of the ‘Outside’ to justify the exorbitant rents of the ‘Inside.’

Safety is the most expensive subscription service in human history. The serf pays for the wall with his liberty, only to find the wall was built to keep him in, not the enemy out.

The relationship is strictly extractive. The platform owner does not produce the content, just as the Lord did not grow the wheat. They merely own the gates. The seated figure’s relaxation is funded by the plowman’s exertion. Every time a creator sells a course, a developer sells a tool, or a user subscribes to a service through the main vein of the ecosystem, the tithe is automatically deducted. It is frictionless extraction. The man under the tree need not even raise his voice; the smart contract—the feudal charter—executes the theft silently.

The Wilderness and the Blue Bubble

The edges of the manuscript are bordered by geometric patterns, distinct from the scene within. These borders represent the limit of the Manor’s jurisdiction. Beyond the manor lay the ‘waste’ or the wilderness. In the medieval mind, the forest was a place of terror—outlaws, beasts, and chaos reigned there. To be banished from the manor was a fate worse than death; it was social and economic non-existence. This fear was cultivated by the Lord to ensure retention. If the outside is terrifying, the heavy tax of the inside feels like a bargain.

We are seeing a return to the fear of the Open Web. Sideloading is framed as dangerous; open protocols are framed as chaotic; the ‘Walled Garden’ is marketed as a sanctuary.

But the most potent lock-in mechanism is social, not technical. In the village, everyone knew everyone. Your reputation was your currency. If you left, you became a stranger, a ‘nobody.’ Today, this dynamic is weaponized through interface design. The ‘Green Bubble’ in a chat interface is not a technical glitch; it is a badge of the exile. It signals to the tribe that this person is outside the walls. They are not ‘one of us.’ They are in the wilderness. The social friction of breaking the group chat is the modern equivalent of the social suicide of leaving the village.

We have reconstructed the medieval village on a global scale, where the fear of social ostracization keeps us paying rent to a landlord we have never met.

The walled garden economy relies on the destruction of interoperability. If you can take your reputation, your data, and your social graph with you, the Lord loses his leverage. Therefore, the walls must be built high. The ‘API limit’ is the height of the castle wall. The lack of a universal standard is the moat. The seated man under the tree smiles because he knows the plowman cannot leave. The oxen are strong, but the wall is stronger.

This feudalism framing is sharper than most takes on walled gardens. The adscripticius glebae parallel really clarifies why data portability isn't just a feature request, it's the difference between tenant and serf. I've watched teams debate whether to rebuild on a new platform vs staying locked in, and the calculation always comes down to sunk cost in propriatary formats. The blue bubble social pressure is genius as a rentention mechanism, way more effective than technical friction alone.