The CEO of War: Why the Condottieri Never Died

The Italian movie poster for ‘I Grandi Condottieri’ inadvertently signals the collapse of the modern nation-state’s monopoly on violence. By analyzing the Renaissance model of the Condottiero—the contractor captain—we reveal a terrifying economic truth: when war becomes an industry, victory becomes bad for business. From the Sforzas of Milan to the PMCs of the modern Sahel, this investigation exposes the inevitable transition from hired gun to sovereign ruler.

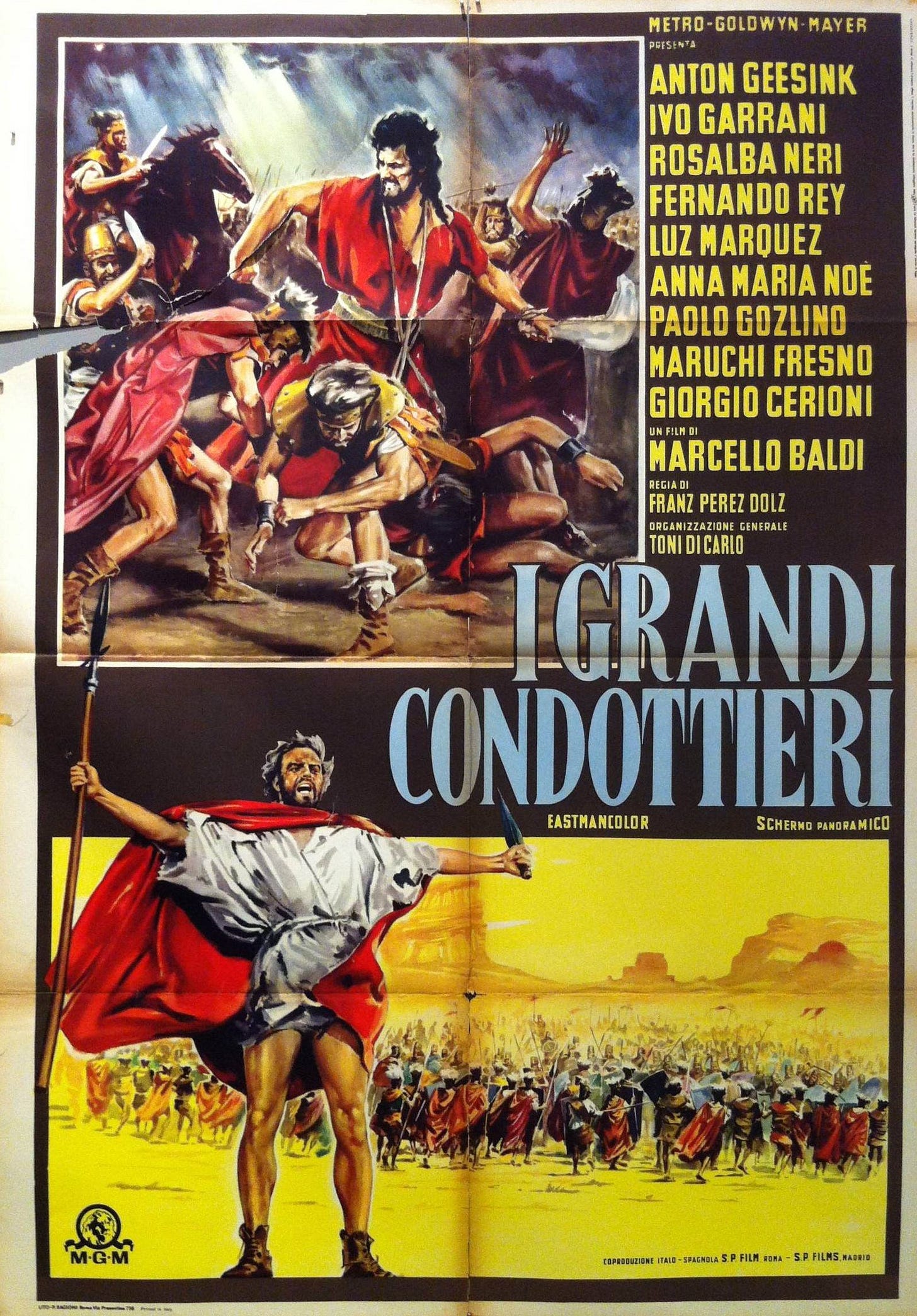

The state represents a monopoly on legitimate violence, or so the Weberian definition claims. Yet, staring at the bold, towering font of *I Grandi Condottieri*, we are reminded of the era when violence was not a duty of citizenship, but a commodity traded on the open market. The poster depicts a romanticized struggle—Anton Geesink’s muscles rippling under Technicolor lighting, a hero leading the masses. But the title betrays the lie. A *Condottiero* was not a patriot; he was a contractor. He held a *condotta* (contract) the way a modern PMC holds a government tender.

A soldier paid by the month prays for a war that lasts forever.

Machiavelli screamed into the void about this danger five centuries ago. He watched as Italian city-states outsourced their defense to captains who had zero incentive to die for Florence or Venice, and every incentive to keep the payroll active. The image above, with its sanitized Hollywood sheen, hides the dirty economic reality of the mercenary era: battles were often bloodless chess matches designed to extend contracts rather than achieve decisive victories.

Peace is the only catastrophe the professional soldier fears. For the Condottiero, a decisive victory is merely a precursor to unemployment.

We delude ourselves thinking this is ancient history. We have returned to the medieval standard. When a superpower hires