The Bureaucracy of Apocalypse

Truman and the Receipt for Total War

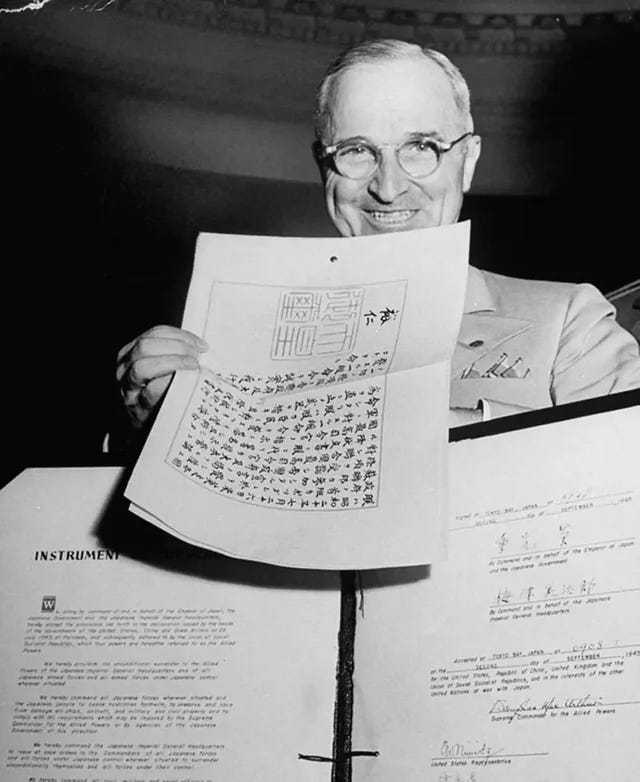

History rarely offers a clean period at the end of a sentence; it usually trails off into an ellipsis of unintended consequences. Yet here, President Harry S. Truman stands as the personification of the definitive, holding the physical manifestation of Imperial Japan’s capitulation. The photograph radiates the exuberant relief of September 1945, capturing the precise moment the bloodiest conflict in human history was transmuted from steel and fire into ink and paper. But look closer at the documents. The large ledger in the foreground is the ‘Instrument of Surrender,’ the legalistic clamp of Allied will. The paper Truman triumphantly elevates, filled with vertical columns of Kanji, is likely the Imperial Rescript—the Emperor’s voice command to his people.

This is not just a photo of victory; it is a portrait of the collision between modern legalism and ancient divinity. Truman’s beaming smile belies the terrifying atomic gamble that made this paperwork possible, suggesting a moral simplicity that the radioactive ruins of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had already permanently complicated.

The Surface Observation

At first glance, this image serves as the ultimate ‘Mission Accomplished’ banner. The composition is hierarchical and stabilizing: the President, centered and illuminated, presides over the chaotic remnants of war which have been neatly bound into the folder labeled ‘INSTRUMENT OF SURRENDER.’ The typography is crisp; the signatures are orderly. It projects the comforting illusion that war is a process with a clear beginning and a distinct end, manageable by reasonable men in suits. > ‘The release of atomic energy has not created a new problem. It has merely made more urgent the necessity of solving an existing one.’ The visual narrative suggests that the problem has been solved. However, this appearance of total control is deceptive. The document Truman holds—the Japanese text—represents the critical, negotiated condition of the surrender: the preservation of the Emperor. The image projects ‘unconditional surrender’ while physically displaying the very condition that ended the war.

The Architect’s Orchestration

The curation of this image is a masterclass in political theater designed for domestic consumption and historical posterity. The photographer captures Truman not looking at the documents, but at *us*—the American public and the wider world. The documents are props in a performance of hegemony. By displaying the Japanese text, the administration is visually confirming the subjugation of the ‘alien’ enemy culture; the vertical script is held in the hands of the Western victor, symbolizing the containment of the East. The framing is tight, excluding the generals and the grim realities of the occupation, focusing solely on the civilian authority. The intention was to reassure a weary populace that the machinery of democracy had successfully ground fascism into dust, validating the unprecedented expense and expansion of state power required to win the war.

The Shadow Records

What lies outside the frame is the terrifying vacuum of power that this paper attempted to fill. The ink on these pages was barely dry, yet the geopolitical concrete of the Cold War was already setting. While Truman smiled, the Soviet Union was aggressively maneuvering in Manchuria and Korea—invasions that actually precipitated the Japanese surrender as much as, if not more than, the atomic bombs. Furthermore, the document conceals the devastation of the Japanese homeland; millions were homeless, starving, and navigating a landscape of cinders. The ‘Instrument’ also hides the massive psychological pivot required of the Japanese people, who had to transition overnight from a death-cult of total war to subjects of a pacifist democracy. We see the triumph of the executive branch, but we miss the birth of the Military-Industrial Complex that would ensure the U.S. never truly demobilized again.

Systemic Analysis

This image documents the precise moment the United States transitioned from a reluctant republic to an imperial hegemon. The sheer bureaucracy visible—the binders, the official seals, the ribbons—signals the rise of the managerial state. The war was won not just by courage, but by logistics and industrial capacity, here symbolized by the neat organization of surrender. This paper trail connects directly to the establishment of the United Nations and the occupation government (SCAP) under MacArthur, essentially rewriting the Japanese constitution. The document is a deed of ownership; it signifies the integration of Japan into the American security architecture, a linchpin relationship that dictates Pacific geopolitics to this day. It validates the system where violence is legitimized through bureaucratic procedure.

Modern Reverberations

In our current era of ‘forever wars’ and ambiguous conflicts that dissolve into insurgencies rather than ending with treaties, the finality of this image feels almost alien. We look at Truman’s confidence with a mix of nostalgia and skepticism. Today, we understand that ‘victory’ is rarely so binary. The legacy of this moment is also the nuclear sword of Damocles that still hangs over us; the authority to use those weapons resided in the office of the man smiling in the photo. The image haunts us because it represents the last time a major power conflict ended with a clear signature, reminding us that modern warfare has lost the ability to close the book.

Truman’s smile is the pivot point of the 20th century. Behind the spectacles and the grin lies the weight of the decision to incinerate two cities to secure the paper in his hands. The document is static, but history is kinetic. The peace it promised was immediate, but the era of anxiety it inaugurated was eternal. > ‘It is not enough to win a war; it is more important to organize the peace.’ The viewer is left to wonder: did the signing of these papers end the violence, or did it merely sublimate it into the terrifying standoff of the next forty years? The ink fades, but the shadow cast by this moment of ‘total victory’ still stretches across the Pacific.