THE ARITHMETIC OF ATROCITY

Uncovering the Bureaucratic Architecture of the Bihar Famine

A forensic reconstruction of the administrative decisions that transformed a meteorological drought into a demographic catastrophe. By analyzing colonial cartography, famine photography, logistical infrastructure, and the rigid legality of relief codes, this investigation reveals that the starvation in Bihar was not a failure of resources, but a successful implementation of extractive policy.

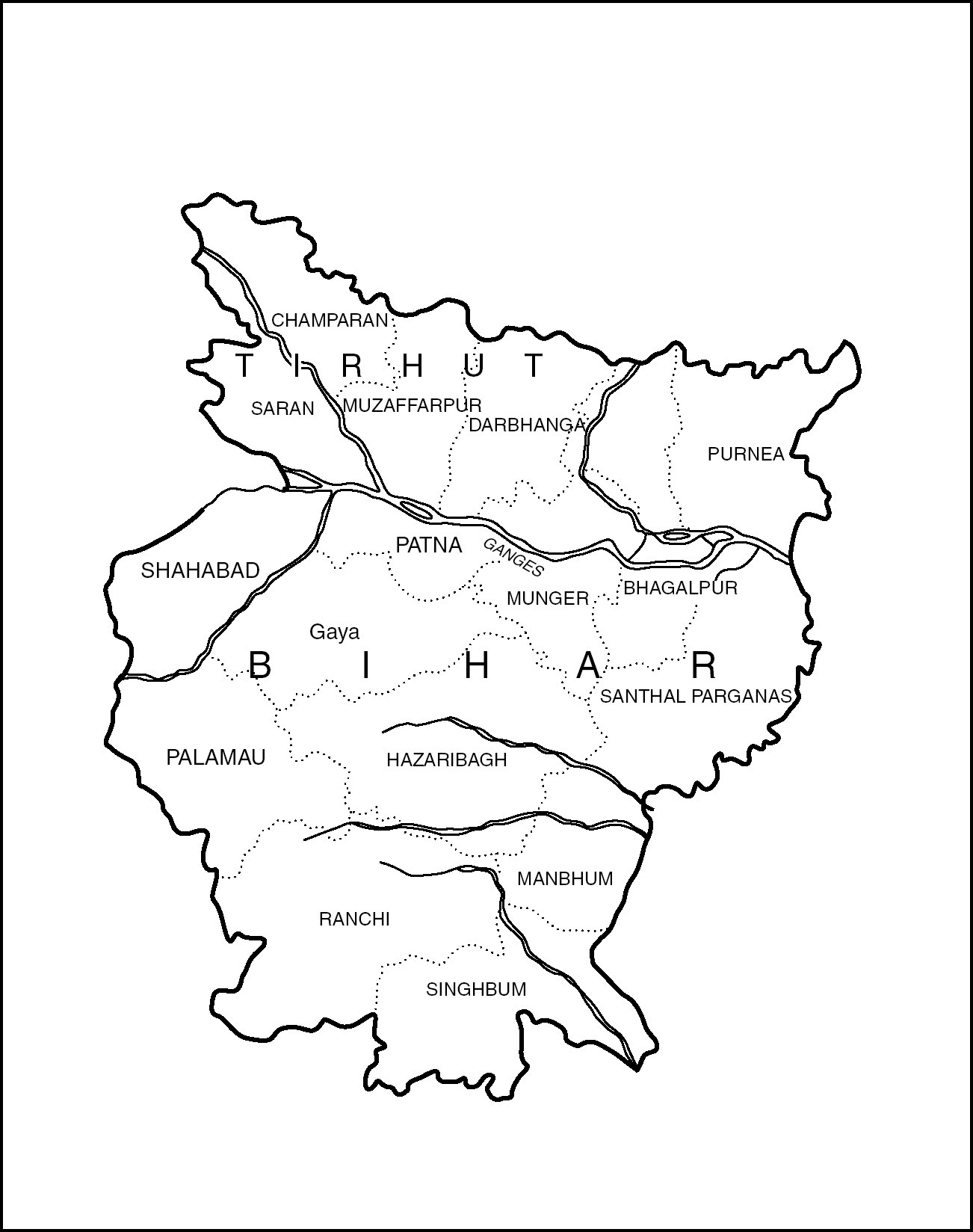

To understand the famine, one must first interrogate the map, not as a geographical tool, but as a blueprint for extraction. The administrative divisions shown here—Patna, Tirhut, Bhagalpur—were not drawn to respect cultural lines or ecological basins; they were drawn to facilitate the efficient flow of revenue. This map is a smoking gun of the colonial restructuring that prioritized the export of opium and indigo over the sustenance of the local population.

Observe the stark delineation of the districts along the Ganges. The river, historically a lifeline for irrigation and transport of local grain, was reimagined by the surveyors as a commercial artery for the metropole. The labels ‘Champaran,’ ‘Saran,’ and ‘Muzaffarpur’ represent zones where the acreage dedicated to food grains was systematically eroded by the forced cultivation of cash crops.

THE MAP DOES NOT SHOW VILLAGES; IT SHOWS TAX ZONES. THE ABSENCE OF HUMAN SETTLEMENT MARKERS INDICATES A VIEW OF THE LAND AS PURELY AN ASSET CLASS, DEVOID OF THE POPULATION THAT WORKED IT.

By fixing these boundaries and enforcing rigid revenue collection within them regardless of yield, the administration effectively decapitalized the peasantry. When the rains failed, the buffer stocks that these districts historically maintained had already been liquidated to pay the tax collector. The cartography itself reveals the logic: the connectivity is lateral, designed to move goods out toward the ports, not internal, to move relief in. This was not merely a map of Bihar; it was a circuit diagram for a wealth pump that had been running at full capacity for decades, leaving the soil exhausted and the granaries empty.

Statistical Obfuscation: The Official Narrative of Denial

Here lies the terrifying disparity between the official report and the physical reality. While the colonial administration was busy drafting memos about ‘scarcity’ and ‘temporary distress,’ the camera captured the absolute biological collapse of the subject. The administrative language of ‘nutritional deficit’ is shattered by the visual evidence of a body consuming itself. The woman and child pictured here are not merely victims of hunger; they are victims of a policy that required ‘rigorous tests’ of starvation before aid could be dispensed. The juxtaposition of the emaciated figures against the cold, stone masonry of the background highlights the durability of the state’s structures against the fragility of the lives it was sworn to protect.

THERE IS NO SUCH THING AS A LOGISTICAL FAILURE IN A FAMINE OF THIS SCALE; THERE IS ONLY THE CALCULATED DECISION THAT KEEPING THE PRICE OF GRAIN STABLE FOR THE MARKET WAS MORE VALUABLE THAN KEEPING THESE SUBJECTS ALIVE.

Who is not visible in this image? The photographer is present, but the relief officer is absent. The framing suggests abandonment—a solitude that belies the fact that this starvation occurred in populous, governed districts. The official statistics released during this period frequently categorized such deaths under ‘cholera’ or ‘dysentery’ to avoid the political liability of ‘starvation.’ This image serves as a primary source correction to the sanitized mortality tables, proving that the ultimate output of the revenue policies discussed in the previous section was not just profit, but necropolitics.

The Infrastructure of Indifference: Railways and the Outward Flow

The railway is often touted as the benevolent gift of modernization, yet this imagery serves as a brutal counter-narrative to that myth. The sheer kinetic power of the locomotive—depicted here as a massive industrial force cutting through the landscape—illustrates the asymmetry of power. The rails were bi-directional in theory but uni-directional in practice: they were efficient at extracting grain from the hinterland to the ports, but bureaucratically sluggish in reversing the flow to bring relief. The irony of modern infrastructure is palpable; the same steel arteries that could have delivered thousands of tons of rice to the starving districts of Bihar were instead prioritized for the movement of troops and export commodities.

SPEED IS A WEAPON. THE EFFICIENCY OF THE RAILWAY NETWORK ACCELERATED THE DEPLETION OF LOCAL STOCKS FASTER THAN TRADITIONAL BULLOCK CARTS EVER COULD, TURNING LOCAL SHORTAGES INTO REGIONAL FAMINES IN A MATTER OF WEEKS.

While this specific visual representation echoes modern freight capacity, it stands as a perfect metaphor for the historical ‘Infrastructure of Indifference.’ The train is a sealed system. It passes through the landscape without interacting with it. The starving populations watching these trains pass saw their own harvest locked behind steel doors, moving toward markets where it would fetch a higher price. The railway effectively integrated the starving peasant into the global market, not as a consumer, but as a casualty of price equilibrium.

The Paperwork of Starvation: The Relief Code as a Tool of Exclusion

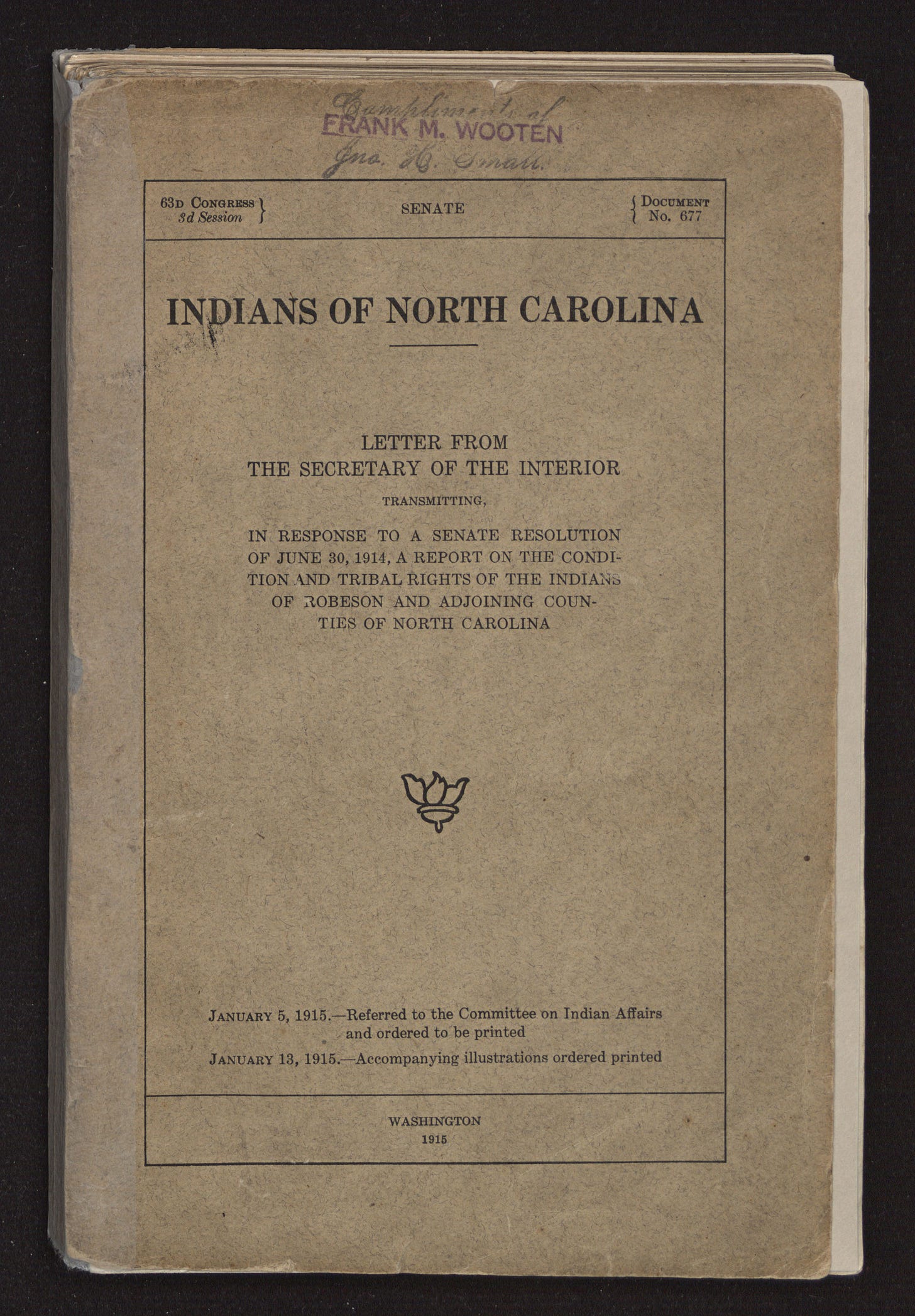

Finally, we arrive at the instrument of execution: the official government report. This document, with its stately serif typography and the imprimatur of the ‘Secretary of the Interior,’ epitomizes the ‘Famine Relief Codes’ that governed life and death. Starvation was not defined by the feeling of hunger, but by the ability to meet the bureaucratic criteria set forth in papers like these. The rigid formatting—’Letter of Transmittal,’ ‘Report on the Condition’—masks the violence of its content. While this specific artifact references the dispossession of indigenous populations in North Carolina, it shares the exact DNA of the colonial Famine Codes applied in Bihar: the reduction of human suffering to an administrative problem to be managed with minimal fiscal outlay.

THE VIOLENCE IS IN THE FONT. THE SANITIZED AESTHETIC OF THE GOVERNMENT REPORT TRANSFORMS MASS DEATH INTO A ‘SENATE RESOLUTION,’ DISTANCING THE POLICYMAKER FROM THE CORPSE.

The text speaks of ‘Tribal Rights’ and ‘Conditions,’ language used universally by imperial administrations to categorize who was deserving of aid and who was distinct, separate, and expendable. The bureaucracy required to produce such a polished report in 1915 implies a vast apparatus dedicated not to solving the crisis, but to documenting it in a way that absolved the state of negligence. This is the ‘paperwork of starvation’—the thick layer of cellulose that insulated the conscience of the ruling class from the reality of the famine zones. The Relief Code was designed to be difficult to trigger; it was a dam built to hold back expenditure, not a channel to release food.