The Architecture of Antifragility

Why the Holy Roman Empire is the Blueprint for the Digital Age

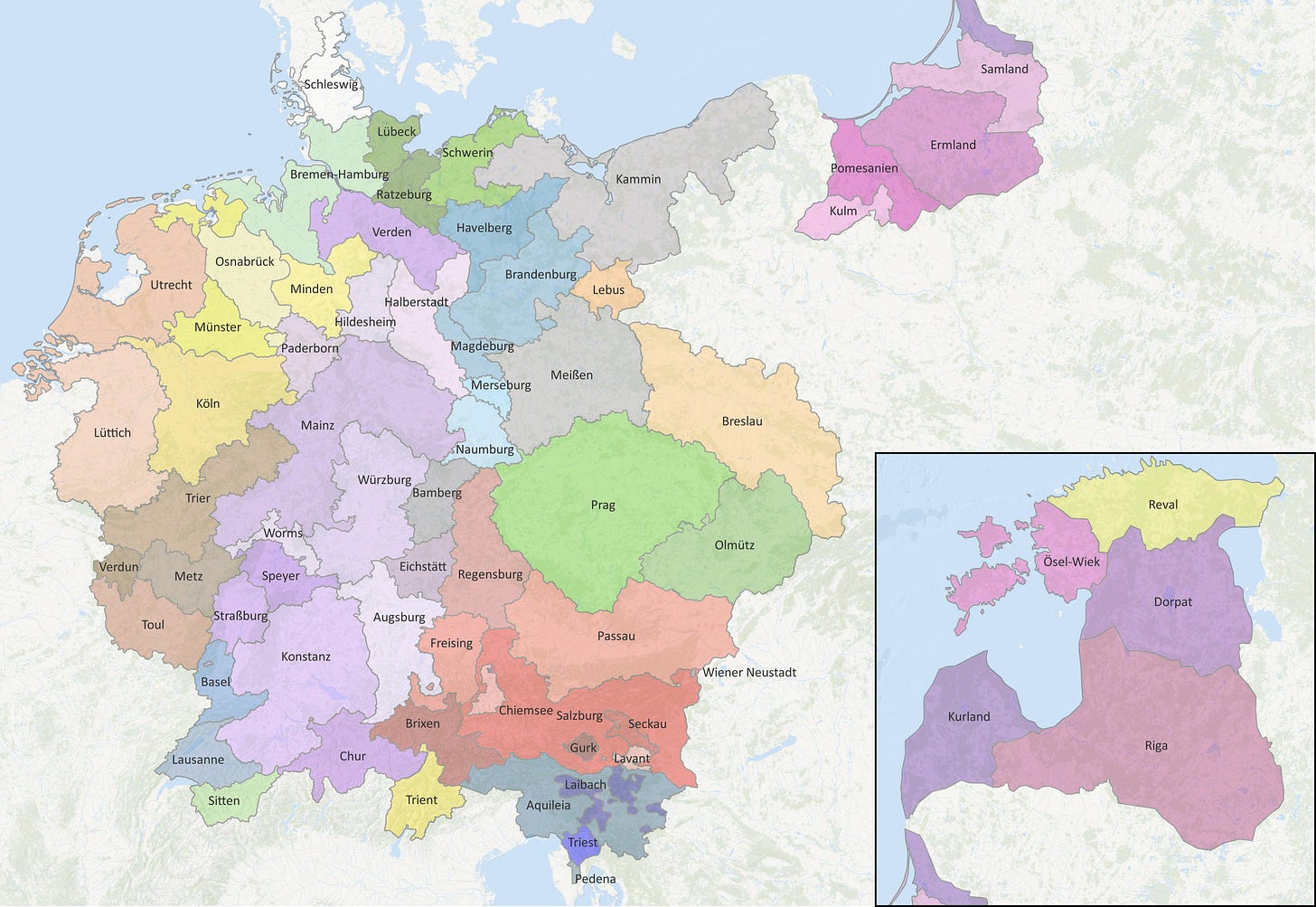

The visual chaos of the Holy Roman Empire’s ecclesiastical map is not a failure of governance, but a triumph of resilience. By analyzing the overlapping jurisdictions of 15th-century Central Europe, we reveal that the HRE was an antifragile market for sovereignty—a feature-rich operating system that offered exit rights, jurisdictional arbitrage, and stability through fragmentation. This investigation argues that the modern fetish for clean borders is a fragile aberration, and the digital future will look remarkably like this medieval past.

To the modern mind, trained on the Westphalian consensus of clear borders and singular sovereignty, the map above looks like a pathology. It appears to be a fractured glass pane, a chaotic jumble of bishoprics, free cities, and principalities that screams ‘inefficiency.’ This reaction is a symptom of the modernist disease: the belief that legibility equals functionality. When we gaze upon the sprawling green expanse of the Archdiocese of Prag or the fragmented violet clusters of Mainz, we are not looking at a broken system. We are looking at a redundant, decentralized network that survived for a millennium while ‘efficient’ empires collapsed around it.

Standardization is the precursor to systemic fragility; the messiness you see here is the firewall against total collapse. Within these jagged lines lies a profound political technology that the 21st century has forgotten: overlapping jurisdiction. In the Holy Roman Empire, a citizen in Mainz or Köln was not merely a subject of a local prince but also a spiritual subject of a Bishop, a legal subject of the Emperor, and perhaps a commercial participant in a Hansa trade guild. If the local lord became tyrannical, one could appeal to the Bishop. If the Bishop overreached, one could appeal to the Imperial Diet.

The HRE was not a state; it was a user interface for navigating competing hierarchies. It was a market for governance where tyranny was checked not by a constitution, but by the sheer availability of alternatives.

This map represents a ‘Sovereignty Stack’ rather than a flat plane of control. The overlapping colors are not errors in painting; they are the visual representation of a system that prioritized individual survival over administrative convenience. The modern state demands you belong to one box. The HRE allowed you to exist in the interstices.

The Sovereignty Stack: A 1,000-Year Protocol for Stability

Focus on the western cluster of the map—Trier, Köln, Mainz, Worms, Speyer. This density of independent ecclesiastical territories acted as the engine room of the Empire. Unlike the centralized stagnation of the French monarchy developing to the West, this region was a pressure cooker of competition. The Archbishops of Mainz were not merely priests; they were Imperial Chancellors and Prince-Electors, wielding power that checked the Emperor himself. This balance of power is visible in the geography. No single entity could expand enough to dominate the system because the cost of conquest was too high in a landscape so densely packed with rival legitimacies.

The Holy Roman Empire was the original blockchain: a distributed ledger of rights and privileges where consensus was difficult, but unilateral alteration was impossible.

Consider the implication of ‘Free Imperial Cities’ scattered throughout these dioceses. They paid taxes only to the Emperor, effectively operating as autonomous city-states within the geographic borders of other principalities. This created a competitive market for human capital. If a Prince in Württemberg raised taxes too high, artisans could migrate to a nearby Free City or an ecclesiastical territory like Augsburg or Konstanz. The map’s fragmentation was a feature that enforced a cap on extraction rates.

Monopoly governance leads to stagnation. The HRE’s chaotic patchwork forced rulers to compete for subjects, sparking the economic engines that would eventually fuel the Northern Renaissance.

When you look at the jagged borders of Salzburg or the isolated enclave of Bamberg, you are seeing the physical scars of liberty. These borders were not drawn by a surveyor in a capital city; they were etched by centuries of negotiation, lawsuits, and local resistance. It is messy because human freedom is messy. Order is the aesthetic of the prison.

The Livonian Sandbox: Innovation at the Bleeding Edge

The inset map of Livonia—modern-day Estonia and Latvia—reveals an even more radical experiment in decentralized governance. Here, the Teutonic Order, the Archbishopric of Riga, and the Bishoprics of Dorpat and Ösel-Wiek formed the Livonian Confederation. This was a frontier society, the ‘Wild East’ of medieval Christendom, where the rules of the core Empire were rewritten. Notice the stark separation of Kurland, Riga, and Dorpat. This was a colonized space governed by military orders and prince-bishops, operating almost entirely independently of the German core yet spiritually tethered to it.

The frontier is always the laboratory for the future, and Livonia was the beta-test for the networked state. The power dynamics here were fluid, defined by the interplay between the Hanseatic League merchants in Reval and Riga and the military aristocracy of the countryside. It was a corporate state before the invention of the corporation. The governance structure was not based on blood or nationhood, but on contract and divine mandate.

In Livonia, we see the prototype of the Special Economic Zone: a territory carved out of the wilderness, governed by specific distinct charters, operating under a different operating system than the surrounding world.

This fragmentation prevented the rise of a singular despot in the Baltic for centuries. It required the overwhelming, centralized brute force of Ivan the Terrible and later the Swedish Empire to finally smash this delicate lattice. Efficiency eventually conquered the Livonian complexity, but it brought with it serfdom and stagnation. The map reminds us that resilience often looks like disunity to the imperial eye.

The Stagnation of Order: A Warning from the Centralized West

While the Holy Roman Empire reveled in the chaotic vibrancy depicted in this map—from the shores of Pomeralia to the Alps of Brixen—its neighbors were pursuing a different path. France and England were consolidating. They were erasing the local duchies, standardizing the laws, and building the machinery of the Leviathan. Historians often praise this ‘state-building’ as progress. This investigation rejects that premise. The centralization of France under the Valois and Bourbons turned the nation into a brittle monoculture, leading inexorably to the totalitarian terror of the French Revolution.

The HRE avoided a ‘French Revolution’ because it never allowed a ‘French Monarchy’ to exist. There was no single head to chop off, no single center of gravity to seize. The Revolutionaries of 1789 looked at the map of Germany and saw backwardness; they failed to see a distributed network that was immune to the systemic shocks that destroyed Paris. The HRE did not collapse from internal contradictions; it had to be destroyed from the outside by Napoleon, the ultimate agent of centralizing modernism.

The modern nation-state is a single point of failure. The HRE was a mesh network.

By viewing this map as ‘backward,’ we adopt the gaze of the conqueror. We side with the simplistic desire for control over the complex reality of organic human organization. We must stop apologizing for the ‘mess’ of the HRE and start recognizing it as the only political structure that successfully balanced scale with local autonomy.

The New Imperial Diet: Algorithms and Anarchy

We are currently witnessing the end of the Westphalian interlude. The era of the centralized nation-state—a mere 300-year blip in human history—is dissolving. The internet is rebuilding the Holy Roman Empire. Look at the digital landscape: we have the return of overlapping jurisdictions (DAOs, Discords, Network States), non-territorial sovereignty (crypto-currencies), and a new class of Prince-Bishops (tech oligarchs and protocol architects). The map of the future will look exactly like the map of 1500.

We are returning to a world where you will hold citizenship in multiple, overlapping clouds, just as a burgher in Lübeck held allegiance to the City, the League, and the Emperor.

This is not a regression; it is a restoration of the natural order. The centralized state was an industrial-age artifact, necessary for mass mobilization and factory standardization. The information age favors the swarm. It favors the patchwork. It favors the model of the Holy Roman Empire. The ‘Imperial Diet’ is now the global discourse on Twitter/X, a noisy, chaotic, powerless-yet-powerful forum where consensus is hammered out in public view.

Don’t fear the fragmentation. Embrace the local liberty it offers. The chaos of the map is the chaos of life itself, resisting the dead hand of the planner.

The map of the HRE is not a relic. It is a blueprint. The Neo-Institutionalists and Digital Architects reading this must understand: Your goal is not to build a new Rome with a single Caesar. Your goal is to build a new Mainz, a new Lübeck, a new Riga. Construct the enclaves. Let the borders overlap. Let the system be messy. In that mess lies the only true freedom.