Shocking History: Why 1900s French Knife Grinders Worked Lying on Their Stomachs

History often confronts us with practices that seem utterly alien, even disturbing, through the lens of contemporary understanding. Few images encapsulate this jarring disconnect more powerfully than that of the early 20th-century French knife grinder, the rémouleur, working not standing or sitting, but lying prone on their stomach, often mere inches from a rapidly spinning grindstone. This wasn't an isolated eccentricity; it was a widespread, established method within certain regions and workshops. To modern eyes, conditioned by decades of occupational health and safety regulations and ergonomic studies, the sight is bewildering. It begs the question: why would anyone adopt such a seemingly perilous and uncomfortable posture for demanding physical labor?

The answer isn't simple sensationalism but lies deep within the confluence of technology, tradition, economics, and a fundamentally different relationship between the human body and industrial work that characterized the era. Unpacking this practice reveals much about the harsh realities of early industrial craftsmanship and the incredible, often dangerous, adaptations workers made to ply their trades.

The Mechanics of the Prone Position

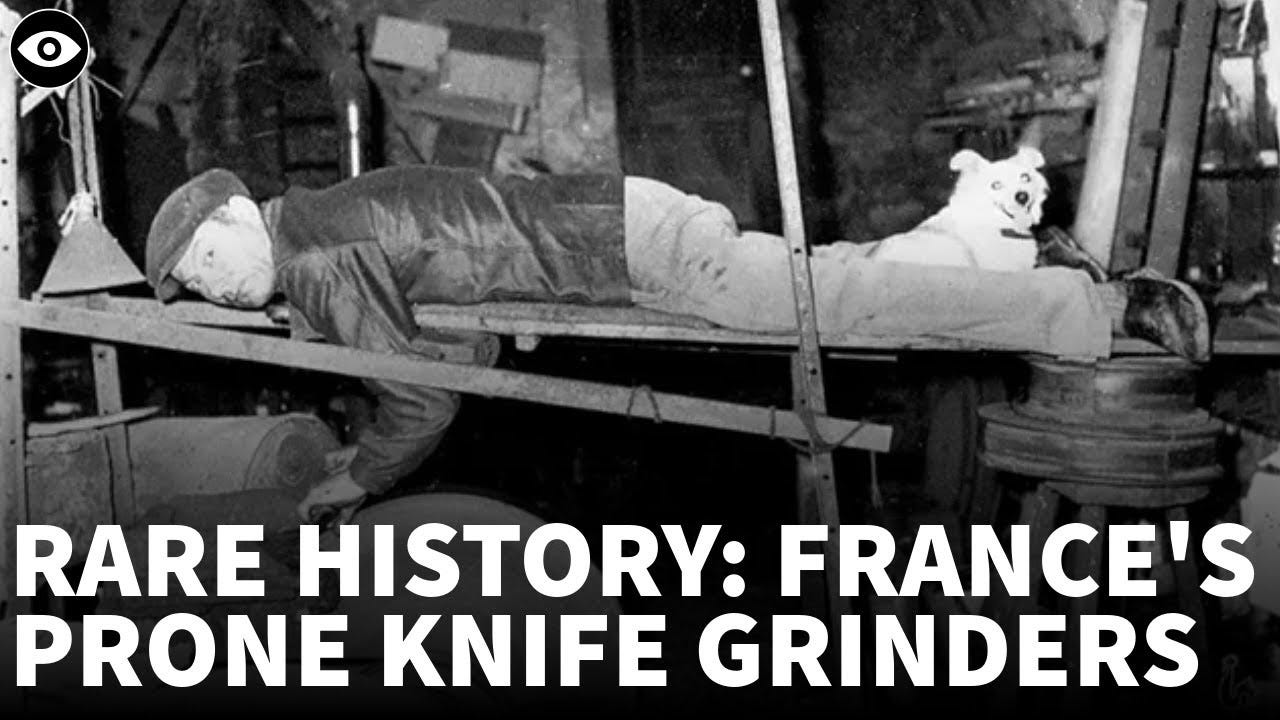

To understand the rationale, we must first visualize the setup. The grinding wheels, often large and water-cooled (or sometimes dry), were frequently oriented horizontally or set low to the ground. The grinder would lie face-down on a plank or bench, sometimes angled slightly downwards towards the wheel. Their arms would reach forward to manipulate the blade against the spinning stone, while their legs might brace against a support or simply hang. Often, adding to the strangeness, a dog would lie *on top* of the grinder's legs or back. This wasn't for companionship; the dog's weight was believed to provide warmth and potentially subtle counter-pressure or stability, though its efficacy remains debated and speaks volumes about the rudimentary understanding of biomechanics at the time.

So, why this specific orientation? Several interconnected factors contributed:

Leverage and Pressure Control: Lying prone allowed the grinder to use their body weight more effectively to apply consistent and precise pressure to the blade against the stone. This was crucial for achieving the correct bevel and sharpness, especially on larger or specialized blades common in agricultural or butchery contexts. The angle enabled a direct, downward force application that might have been harder to sustain accurately while standing or sitting with the machinery available then. It allowed for a unique kind of *kinesthetic intimacy* with the task, feeling the grind through their entire upper body.

Machinery Design and Workshop Layout: Early grinding machinery, particularly water-powered setups, often featured large, horizontally mounted stones driven by belts and shafts positioned low down. The prone position may have simply been the most direct and efficient way to interact with this existing infrastructure. Workshops were often cramped, and this posture might have been a space-saving adaptation, allowing multiple grinders to work in relatively close proximity.

Control Over Fine Motor Skills: With the body stabilized in the prone position, the grinder could potentially dedicate more fine motor control to their hands and arms, necessary for the delicate task of shaping and sharpening an edge without overheating or damaging the steel. The stability offered by lying flat might have surpassed what a simple stool could provide, especially during long hours of work.

The Brutal Reality: Danger and Disease

While there might have been perceived technical advantages, the human cost of this practice was immense and undeniable. The position itself fostered a host of physical ailments. Chronic back and neck pain were near certainties. The constant vibration from the grinding wheel transmitted through the worker's body likely contributed to nerve damage and musculoskeletal disorders. But the most insidious danger was respiratory.

Knife grinding produced a constant shower of fine particles – metal dust from the blade and, more dangerously, silica dust from the sandstone grinding wheels. Inhaling these particles day after day led inevitably to silicosis, a devastating and incurable lung disease known colloquially in France as *“la maladie du chien”* (the dog’s disease, perhaps grimly referencing the dogs sharing their workspace, or the dog-like panting breath it caused) or more broadly as *grinder's asthma* or *potter's rot* in English-speaking contexts. Lying prone potentially placed the grinder's face closer to the source of this dust, exacerbating inhalation.

"The lifespan of a grinder was notoriously short... The dust penetrated everything, coating the lungs, leading to a slow, agonizing suffocation. It was a trade that consumed its practitioners." - Historical accounts often reflect this grim reality.

Furthermore, the proximity to the spinning stone carried the constant risk of catastrophic injury. A broken wheel, a slipped blade, or ejected metal shards could cause severe trauma, eye injuries, or even death. Safety guards, if they existed at all, were rudimentary. This wasn't just work; it was a daily gamble with life and limb, undertaken out of economic necessity.

To truly appreciate the physicality and the almost surreal nature of this working method, seeing it in motion is essential. The surviving footage offers a stark window into this vanished world, revealing the intense concentration, the physical strain, and the hazardous environment these artisans endured. It transforms an abstract historical fact into a visceral human reality.

Viewing this footage forces a confrontation with the material conditions of past labor. It underscores how profoundly our expectations of work, safety, and the value of human well-being have shifted, largely due to the struggles of organized labor and advancements in technology and ergonomic understanding.

Contextualizing the Craft: Tradition and the Industrial Age

This practice didn't emerge in a vacuum. It was embedded within specific craft traditions, particularly in French cutlery centers like Thiers, known for centuries as the heartland of knife production. Skills were passed down through generations, and established methods, however dangerous, often held the weight of *tradition*. Change comes slowly to such environments, especially when altering established techniques might be perceived as compromising quality or efficiency in a highly competitive trade.

Moreover, this period represents a transitional phase in the Industrial Revolution. While mechanization was present (water or early electric power), the sophisticated understanding of *ergonomics* and *occupational safety* that we take for granted today simply did not exist. The primary focus was on production output, often at the expense of the worker's health. The human body was viewed more as an adaptable component of the production process, expected to conform to the machine, rather than designing the machine around human needs and limitations. This perspective, arguably echoing certain aspects of Marx's critique of *alienated labor*, saw the worker subsumed by the demands of the industrial apparatus.

The economic pressures on these artisans were also immense. Knife grinding was often poorly paid, piece-rate work. Maximizing output was essential for survival, potentially reinforcing the use of techniques perceived, rightly or wrongly, as faster or more effective, regardless of the long-term health consequences. There was little regulatory oversight and few alternatives for those skilled in the trade.

A Legacy Etched in Stone and Dust

The image of the prone French knife grinder serves as a potent historical artifact. It challenges our assumptions about work and progress, reminding us that the past is not merely a quaint prelude to the present but a landscape of radically different – and often brutal – realities. The practice eventually faded with advancements in grinding technology (vertically oriented wheels, better dust extraction), a growing awareness of occupational diseases, and stronger labor protections.

Yet, reflecting on why these workers lay on their stomachs is more than just uncovering a curious historical footnote. It is an exercise in understanding the complex interplay between technology, necessity, tradition, and the profound resilience – and vulnerability – of the human body in the face of industrial demands. It prompts us to consider the hidden costs often embedded in the objects we use daily and the long, hard-fought journey towards safer and more humane working conditions.

The ghosts of the *rémouleurs*, forever bent over their grinding stones in a cloud of lethal dust, compel us to ask not only how far we've come, but what unseen compromises might still linger in the shadows of our own modern production systems.