Retro Ads: Unmasking Sexism in Marketing

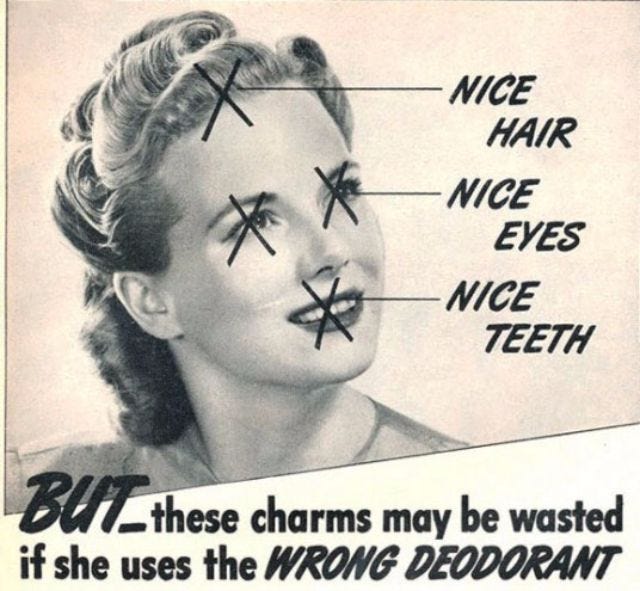

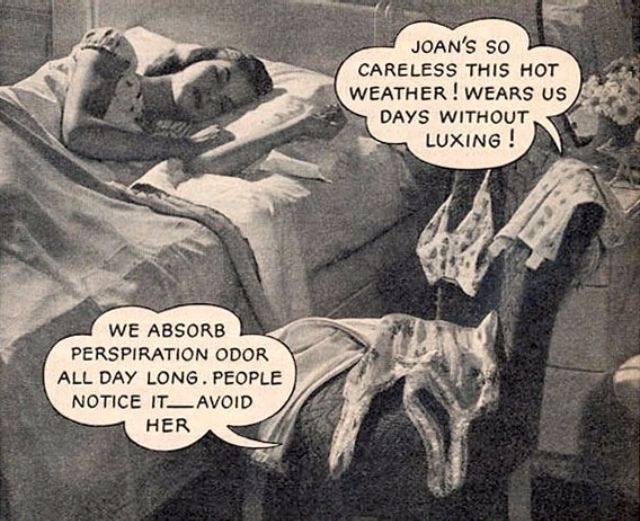

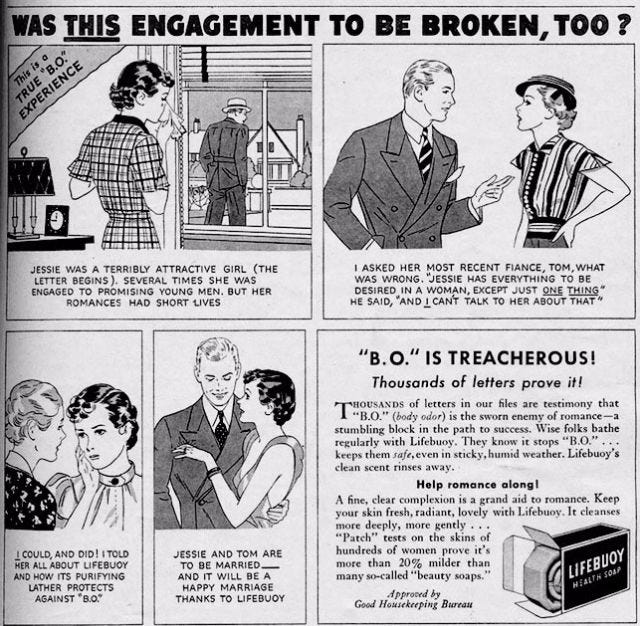

Beyond weight concerns, women were pressured by ads to fear their own natural body odor.

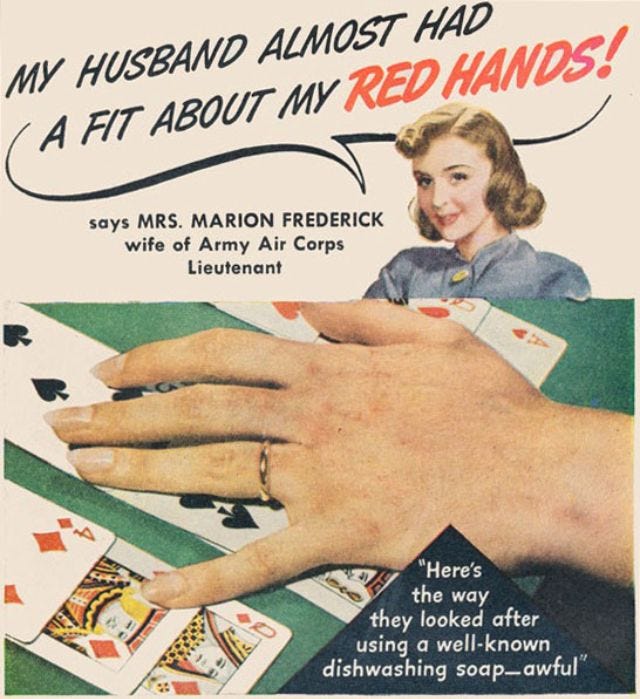

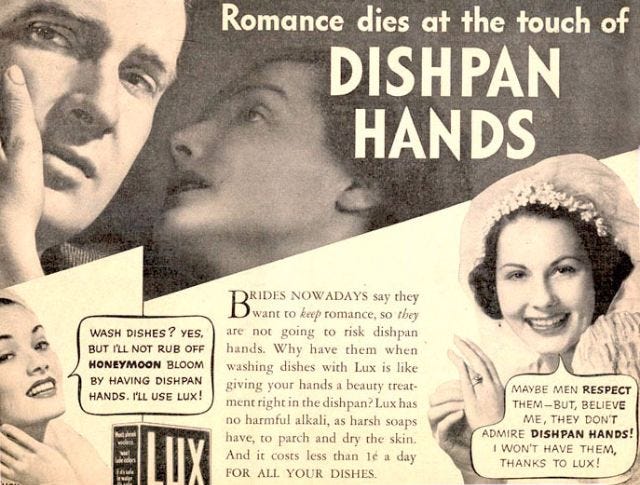

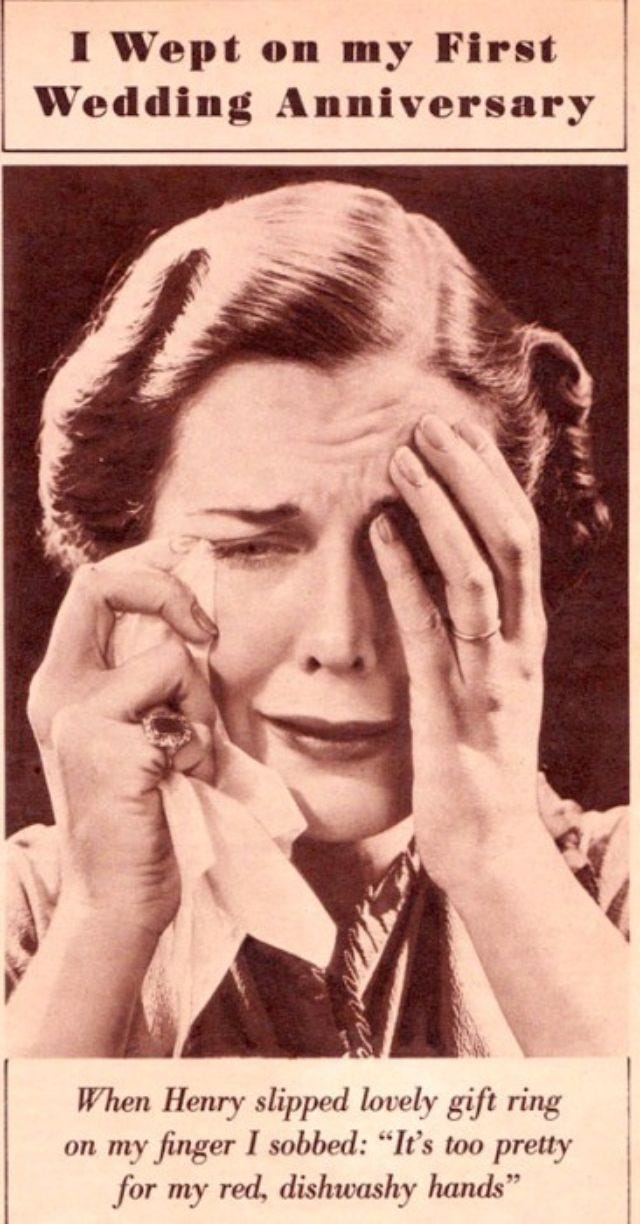

Ads claimed 'dishpan hands' were 'traumatic' to husbands, who, ironically, never lifted a finger for dishes.

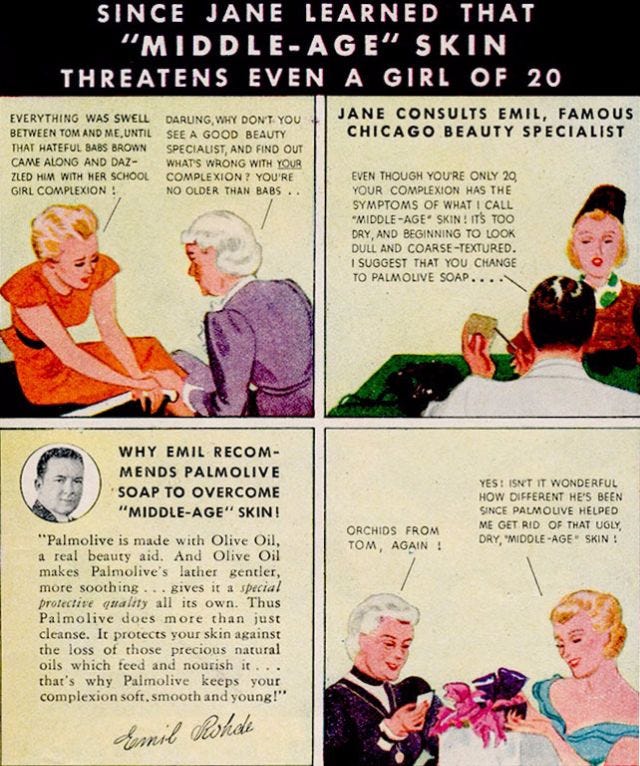

This ad implies a woman of 20 could lose her husband due to 'middle-age skin,' highlighting absurd beauty standards.

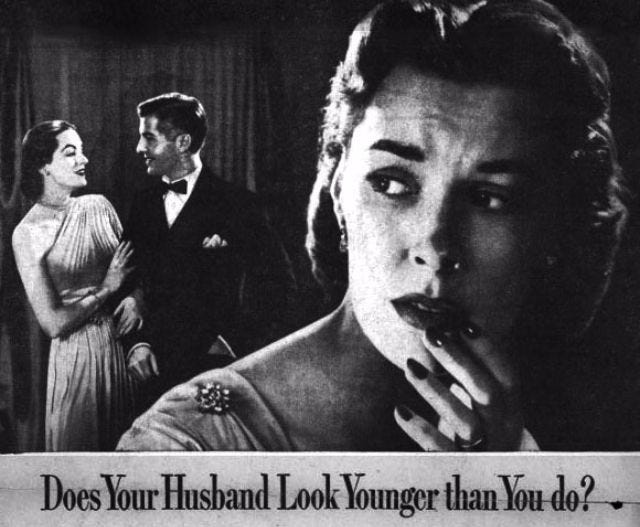

The fearmongering continued: if your husband met a younger-looking woman, your marriage was doomed.

1930s shampoo ads exploited the social importance of dancing, instilling fear of body odor in women.

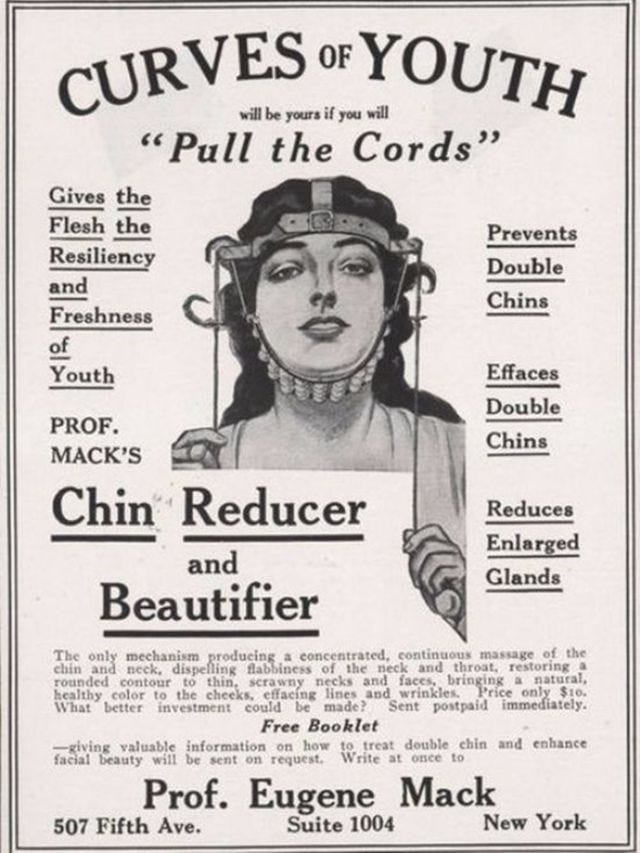

19th-century ads aggressively marketed devices designed to surgically 'reshape' women's faces.

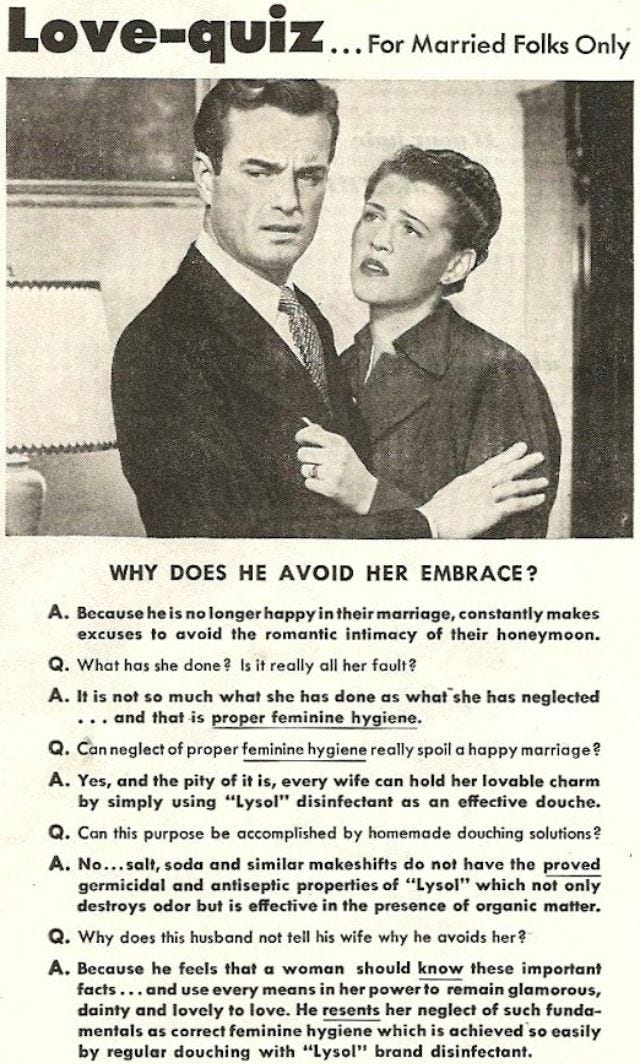

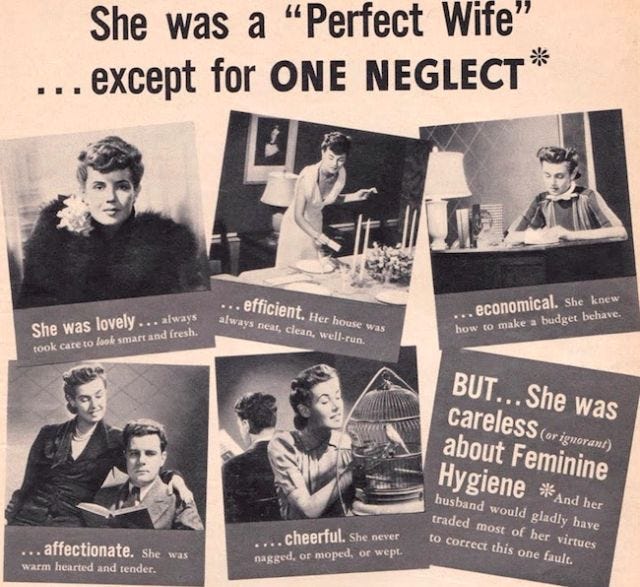

Lysol, marketed as a douche in the 1930s, ran ads depicting husbands abandoning wives over 'feminine hygiene' issues.

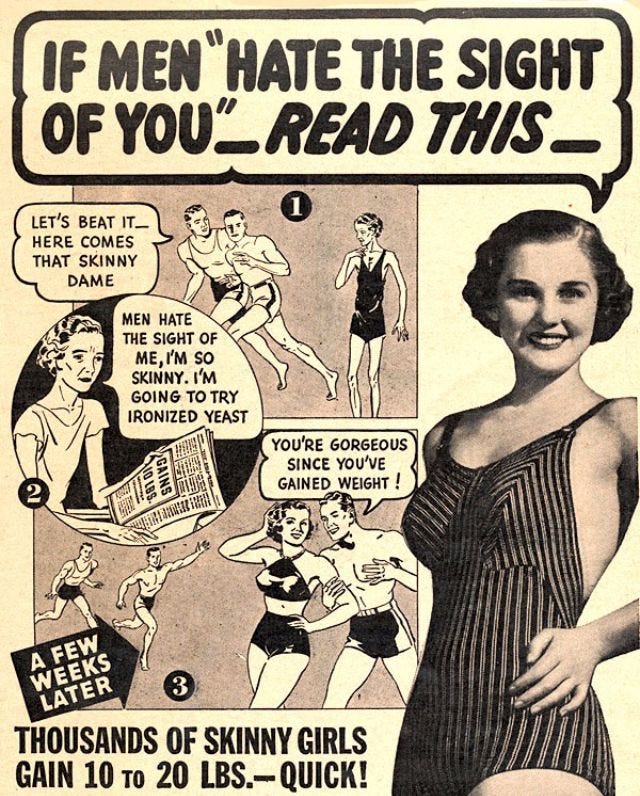

During the Depression, Ironized Yeast ads targeted 'skinny' women, promising 'weight' in the form of larger hips and breasts to fit changing ideals.

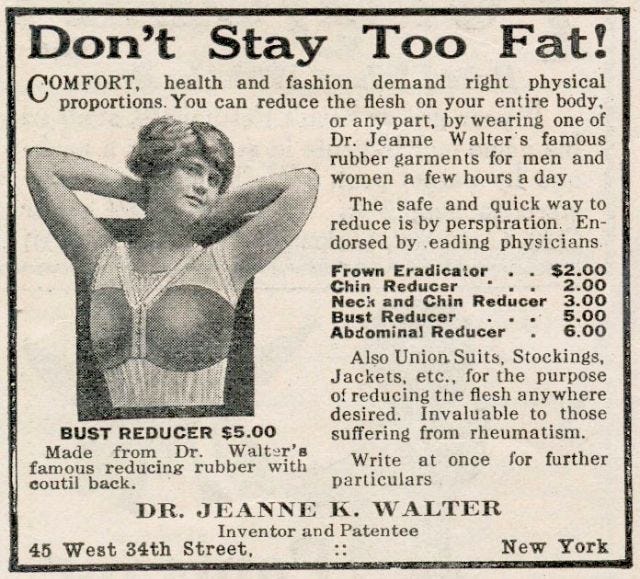

This 19th-century device, promising to shrink the bust, suggests Victorian ideals sometimes favored a smaller chest for the hourglass figure.

1930s advertisers invented 'S.A.' (Stocking Appeal) to pressure women into obsessing over perfect stockings, fearing husband's disapproval.

1930s ads demonized 'dishpan hands,' portraying them as a direct threat to marital harmony.

An ad shows 'pretty Joan' baffled by her unpopularity, unaware her animated undergarments are gossiping about her poor hygiene.

This ad critiques a 'girl in a million' for 'gap-osis' (gaps in her skirt buttons), implying it ruins all her other qualities.

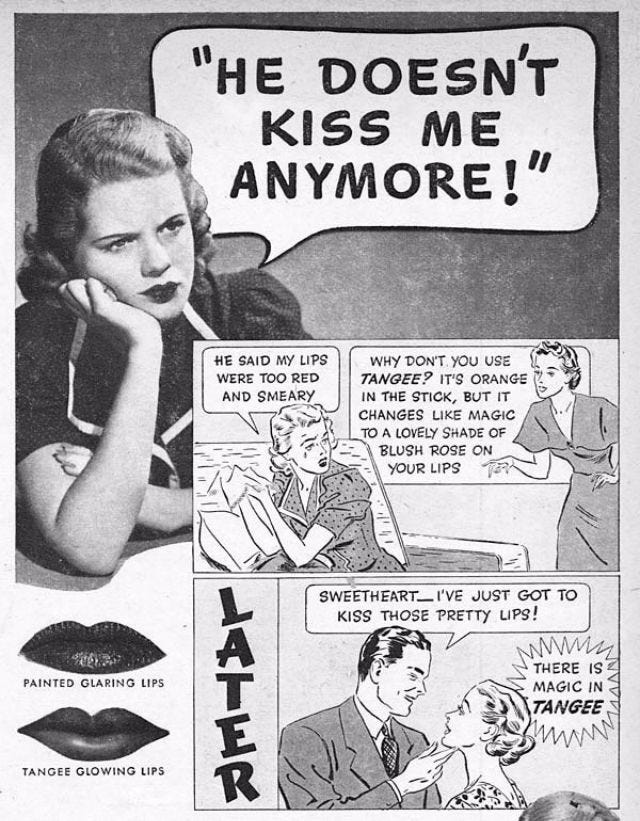

1930s Tangee ads warned women that lips could be 'too red,' 'smeary,' or 'painted' for a man's kiss, promoting a 'natural' look.

Eastern Airlines' 1970s stewardess qualifications: a degrading checklist of physical attributes, revealing rampant sexism in hiring.

This 1930s Lysol ad subtly promoted the product as both a vaginal deodorant and a dangerous contraceptive spermicide, hinting at 'organic matter'.

An alarming Lysol ad implies that proper 'feminine hygiene' transforms an angry husband into a loving one.

This particular 1930s Lysol ad serves as a shocking catalog of the era's patriarchal expectations for wives.

Lysol ads repeatedly linked 'feminine hygiene' failures to husbands becoming distant and cold.

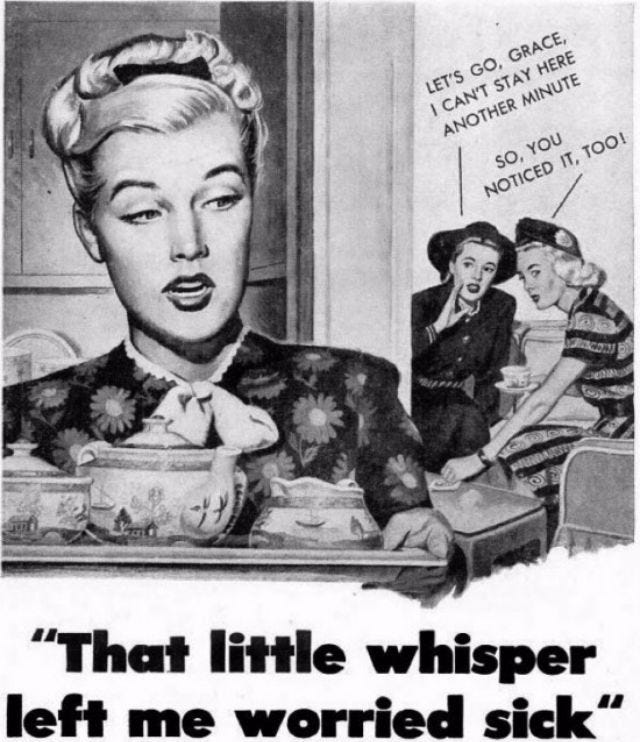

Beyond vaginal odor, women were also bombarded with ads making them paranoid about bad breath.

Ads shamefully suggested even 'lovely ladies' were ignorant about basic personal hygiene.

Advertisers used peer pressure, warning women that not using the 'right' soap or deodorant would lead to social ostracization.

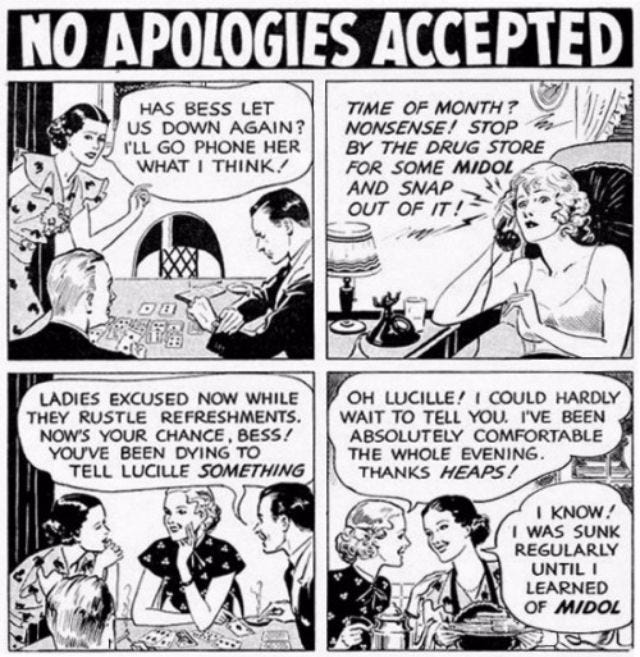

Early Midol ads pushed women to ignore period discomfort and maintain productivity, reinforcing societal expectations.

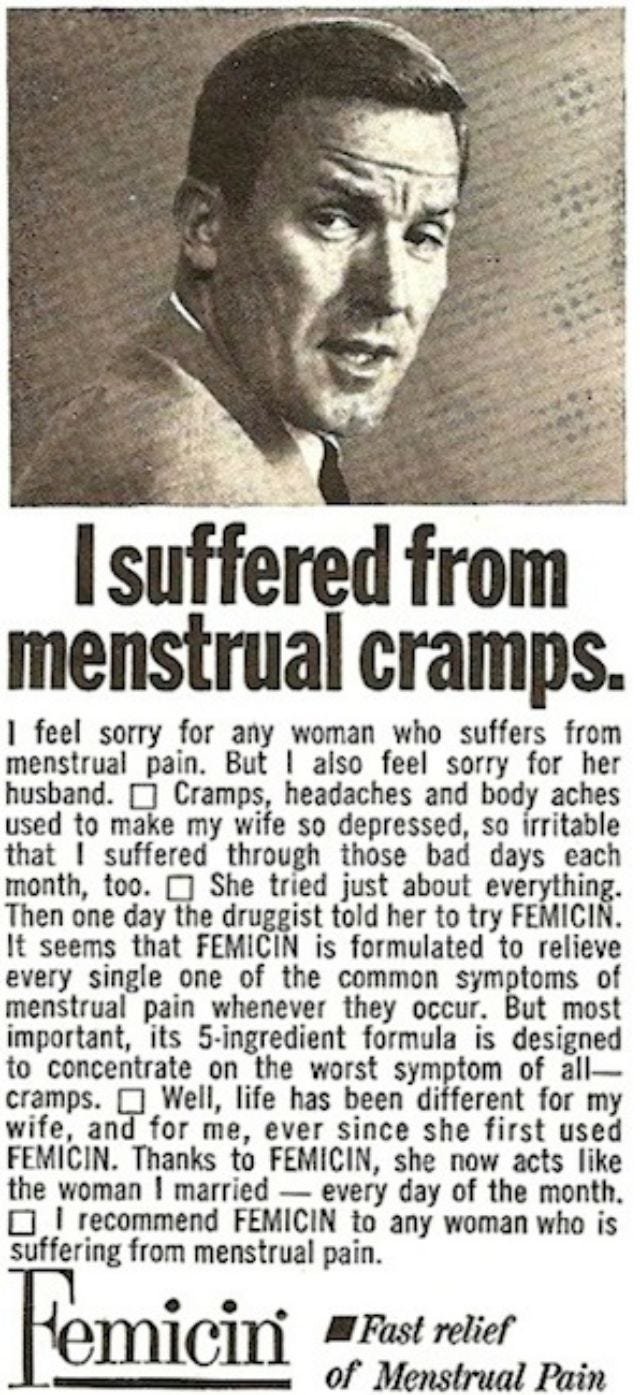

Ads bizarrely suggested that women experiencing periods had a duty not to 'make men suffer' due to their discomfort.

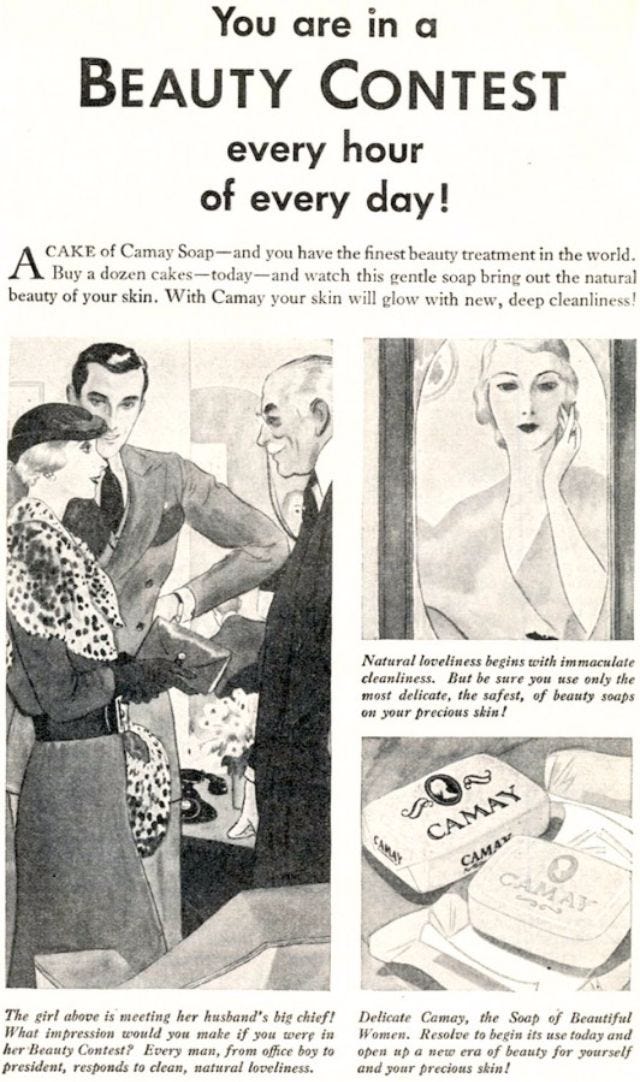

An ad depicts a woman pressured to maintain youthful beauty, not for herself, but to impress her husband's boss.

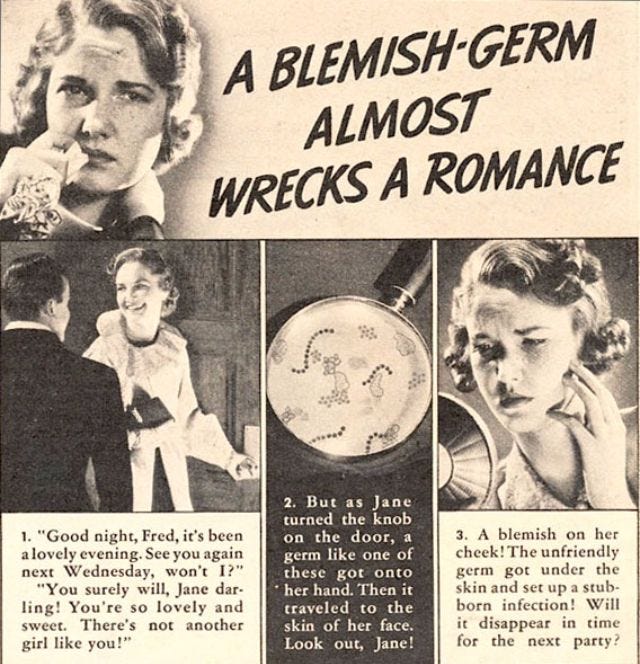

A 1930s ad fearfully claimed a single zit could instantly sabotage a budding romance.

Under intense advertising pressure, a woman with acne is shown retreating, highlighting the emotional toll of unrealistic beauty standards.

This ad directly equates 'Love, Romance, Popularity' with 'feminine charm,' specifically defining it as 'a full, shapely bust'.

Paradoxically, another ad warns that a woman's chest-line could 'bulge too much,' showcasing conflicting body ideals.

Regardless of bust size trends, the relentless pressure to hide and control the belly remained a constant for 20th-century women.

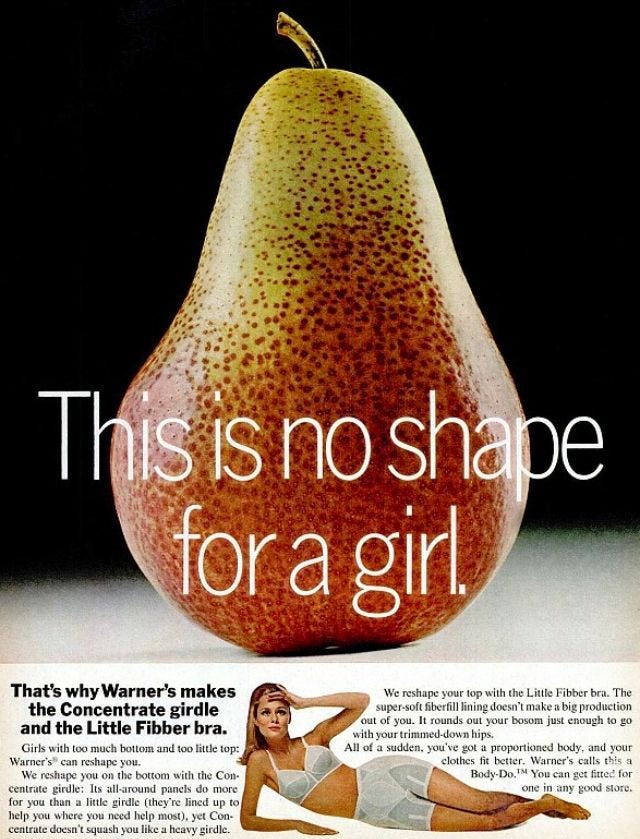

Even by the 1970s, ads continued to push products promising to sculpt the female body into an 'ideal' shape.

This ad ludicrously claims constipation doesn't just cause discomfort, but also destroys a woman's personality and dating prospects.

The plight of 'dishpan hands' was exaggerated to such an extreme that ads depicted women crying over them.

Aging was presented as a significant professional liability for women in the workforce, reflecting ageist biases.

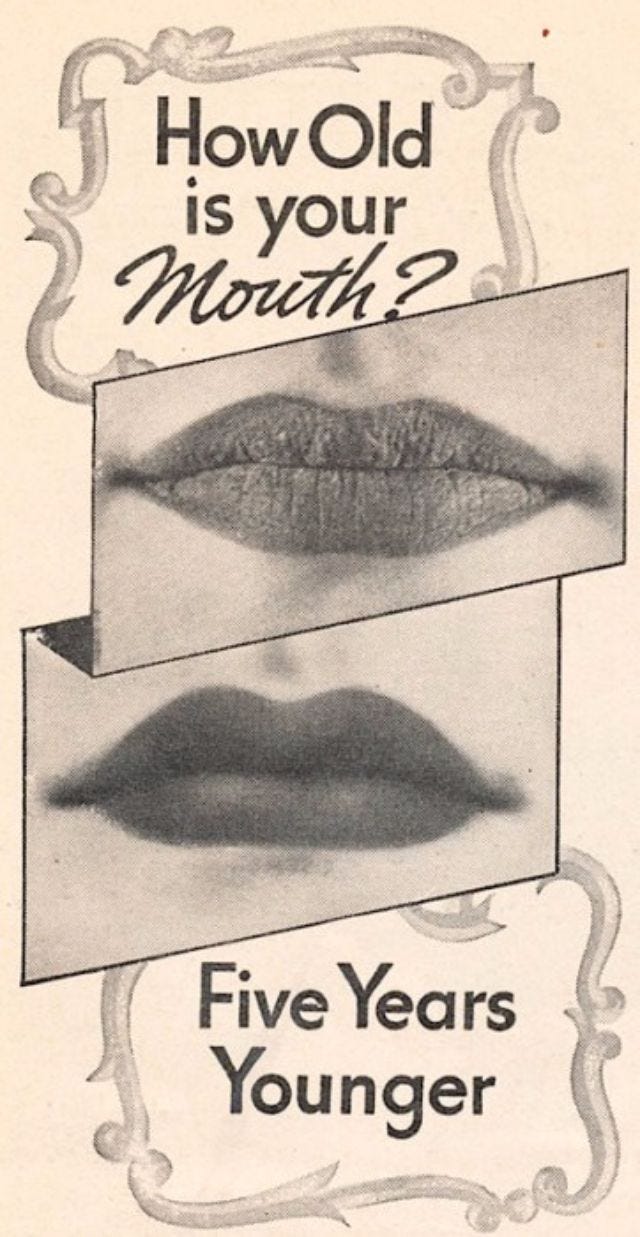

Advertisers even managed to instill anxiety in women about the perceived smoothness of their lips.

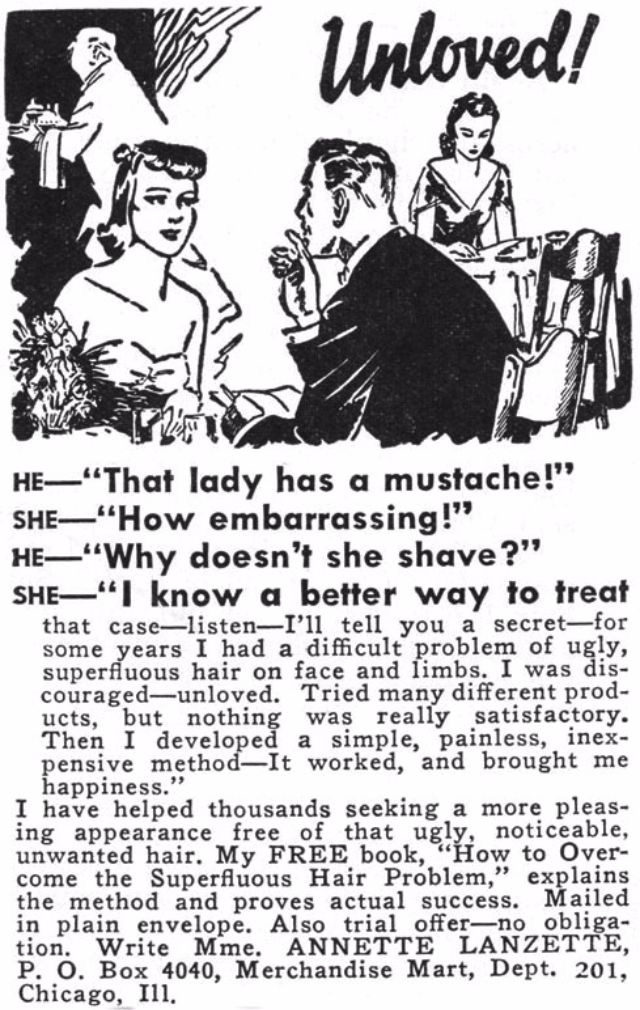

An ad shows a couple cruelly gossiping about an 'unloved' woman, implying her facial hair is the cause of her social isolation.

Despite all these beauty pressures, ads paradoxically dictated that a woman must never appear vain.

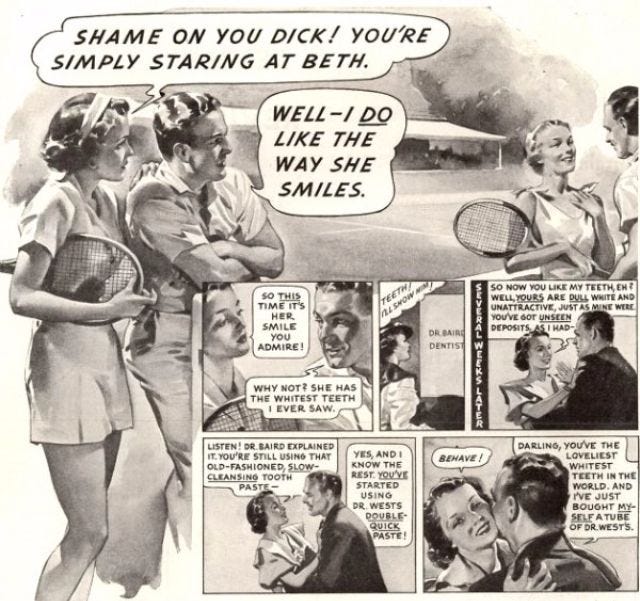

Many ads implied husbands had a 'wandering eye,' easily tempted by trivial physical imperfections like less-than-white teeth.

The 'perfect woman' in these ads was portrayed as serving 'he-man' food, avoiding 'sissy-sweet salads' to cater to male preferences.

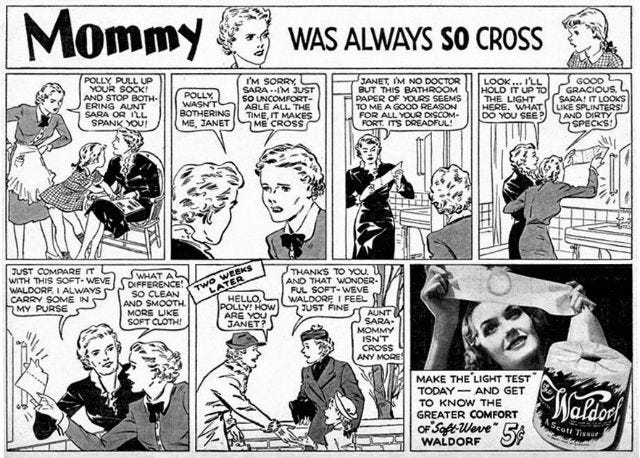

A 1930s Waldorf ad series absurdly linked the quality of toilet paper to the harmony and breakdown of family life.