Heisenberg: Hero or Villain? The Shocking Truth About His Role in WWII's Atomic Bomb Race

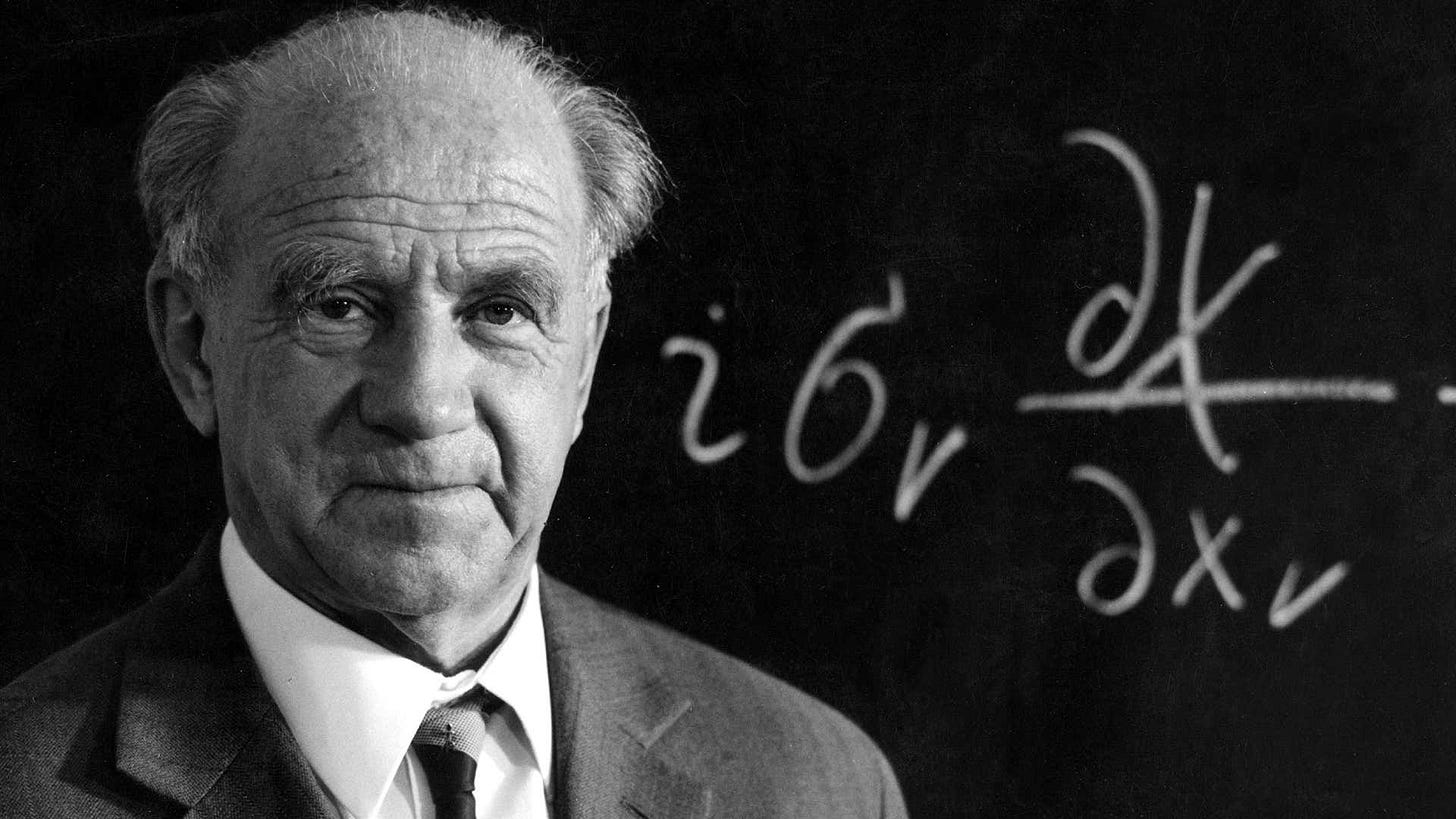

The name Werner Heisenberg resonates through the annals of physics, forever linked with the revolutionary *Uncertainty Principle* that fundamentally altered our understanding of the quantum world. Awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1932, he was a towering figure, a national icon in Germany. Yet, his legacy is irrevocably tangled with one of history's darkest chapters: the Second World War and the terrifying race to develop the atomic bomb. Was Heisenberg a patriot forced into an impossible situation, subtly sabotaging the Nazi war machine from within? Or was he an ambitious scientist willing, perhaps even eager, to deliver the ultimate weapon to a genocidal regime? The question of Heisenberg: hero or villain, remains one of the most profound and unsettling enigmas of the 20th century.

Peeling back the layers of wartime secrecy, post-war justifications, and conflicting testimonies reveals a picture far more complex and morally ambiguous than any simple label can capture. The "shocking truth" isn't a clean verdict, but rather the disturbing realization of how genius, ambition, nationalism, and morality can collide under extreme pressure.

The Pre-War Luminary and the Rise of Nazism

To understand Heisenberg's wartime role, we must first grasp his stature. He wasn't merely *a* physicist; he was one of *the* leading theoretical physicists globally. His work laid crucial groundwork for quantum mechanics. However, his rise coincided with the ascent of the Nazi Party. While not an ardent Nazi himself – indeed, he faced attacks from proponents of *Deutsche Physik* (German Physics) who denounced his work and Einstein's as "Jewish Physics" – Heisenberg was also a staunch German patriot. He believed in German culture and science and made the fateful decision to remain in Germany after 1933, unlike many colleagues (including Einstein, Schrödinger, Born, and Bohr's protégé Lise Meitner) who fled persecution.

His decision to stay placed him in a precarious position. He navigated the treacherous political landscape, sometimes defending modern physics against ideological attacks, sometimes making compromises to protect his position and the future of German science as he saw it. This complex balancing act foreshadowed the even more profound moral dilemmas he would face during the war.

Leader of the *Uranverein*: The German Nuclear Program

Following the discovery of nuclear fission by Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann in Berlin in late 1938 (and its theoretical explanation by Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch shortly after), the military potential was immediately apparent. By 1939, Germany had consolidated its nuclear research efforts into the *Uranverein*, or Uranium Club. Werner Heisenberg quickly emerged as a leading theoretical figure within this clandestine project.

The *Uranverein*'s goal was to explore the feasibility of both nuclear reactors (for energy) and nuclear explosives. Heisenberg's group focused on reactor design, exploring heavy water as a moderator, while other groups tackled isotope separation. Compared to the Allies' Manhattan Project, the German effort was significantly smaller, underfunded, plagued by infighting, and hampered by strategic errors, such as prioritizing other weapons systems later in the war.

Central to the debate is the question of intent versus capability. Did the German program fail because its leading scientist, Heisenberg, secretly wanted it to fail, or did it fail simply because of technical hurdles, resource limitations, and scientific misjudgments?

The Copenhagen Enigma: A Meeting Shrouded in Mystery

Perhaps the most scrutinized event in Heisenberg's wartime story is his mysterious visit to his former mentor, Niels Bohr, in Nazi-occupied Copenhagen in September 1941. What exactly transpired during their private conversation remains fiercely debated. Heisenberg, after the war, claimed he went to Bohr seeking guidance and perhaps to suggest a mutual agreement among physicists on both sides *not* to pursue atomic weapons. He hinted that he knew how to build a bomb but was reluctant.

Bohr's recollection, revealed decades later through unsent draft letters, painted a starkly different picture. Bohr remembered Heisenberg boasting about Germany's inevitable victory, confidently stating that Germany was working on an atomic bomb, and possibly sketching a crude reactor design. Bohr was horrified, ending the conversation abruptly and severing their long friendship. Was Heisenberg naively trying to enlist Bohr in a form of scientific arms control, or was he subtly fishing for information about Allied progress, or even attempting to recruit Bohr?

This pivotal encounter lies at the heart of the controversy. Understanding the nuances and interpretations of this meeting is crucial. For a deeper dive into the conflicting accounts and implications of the Copenhagen visit, this visual exploration provides valuable context:

Farm Hall: Eavesdropping on Defeat

After Germany's surrender in 1945, ten prominent German nuclear scientists, including Heisenberg, Hahn, and von Weizsäcker, were secretly interned at Farm Hall, a bugged country house in England. Their conversations were recorded, providing invaluable insight into their mindset and knowledge. The *Farm Hall transcripts* reveal genuine shock and disbelief when the news of the Hiroshima bombing broke.

Heisenberg's initial reaction was skepticism – he didn't believe the Allies could have achieved what the German program had deemed so difficult, particularly regarding isotope separation. Strikingly, in conversations immediately following the news, Heisenberg made significant errors when estimating the critical mass needed for a uranium bomb, suggesting a much larger, almost impractical amount. Within days, however, he had corrected his calculation and delivered a lecture to his fellow detainees outlining the basic principles correctly.

This sequence has fueled endless debate: Was Heisenberg's initial ignorance genuine, proving he hadn't fully grasped bomb physics during the war (thus undermining his post-war claims of moral restraint)? Or was his rapid correction proof that he *did* understand, and perhaps his earlier "failures" within the *Uranverein* were, if not deliberate sabotage, then at least a result of consciously *not* pushing the research aggressively towards a weapon?

Post-War Narratives and Historical Reassessment

In the aftermath of the war, Heisenberg and his colleagues, particularly Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker, constructed a narrative suggesting they had understood the potential for a bomb but had deliberately slow-walked the project for moral reasons, focusing instead on a reactor. This interpretation was popularized by Robert Jungk's 1956 book, *Brighter than a Thousand Suns*. It painted Heisenberg as a quiet hero who denied Hitler the bomb.

However, this narrative was challenged almost immediately, notably by Samuel Goudsmit, the scientific head of the Allied Alsos Mission tasked with investigating the German nuclear program. Goudsmit argued forcefully that the Farm Hall transcripts proved the German scientists simply failed – they didn't fully understand bomb physics, overestimated the difficulties, and lacked the resources. The release of Bohr's draft letters concerning the Copenhagen meeting in 2002 further complicated the heroic narrative, lending weight to the idea that Heisenberg was, at the very least, deeply ambiguous in his wartime actions and communications.

Historians today largely reject the simplistic "moral sabotage" theory. The consensus leans towards a combination of factors explaining the German failure: insufficient resources, scientific missteps (like initially dismissing graphite as a moderator), lack of strong centralized leadership compared to the Manhattan Project's General Groves, Allied bombing campaigns, and perhaps a degree of *ambivalence* on the part of scientists like Heisenberg. He may not have actively sabotaged the project, but he also may not have pushed it with the desperate urgency required, possibly due to a mix of scientific skepticism about its short-term feasibility and underlying moral unease.

Beyond Hero or Villain: The Burden of Ambiguity

Ultimately, labeling Heisenberg as purely a "hero" or a "villain" obscures the profound complexities of his situation. He was a product of his time and place – a brilliant scientist deeply attached to his country, operating under a brutal regime in a total war. His motivations were likely a tangled mix: scientific curiosity, ambition, patriotism, fear, a desire to preserve German science, and perhaps genuine, albeit possibly passive, moral reservations about creating such a devastating weapon for Hitler.

He clearly miscalculated the political and moral landscape, both in staying in Germany and in his interactions like the one in Copenhagen. He likely overestimated his ability to control or influence the direction of the research or the regime's intentions. The *Farm Hall transcripts* suggest a degree of scientific overconfidence mixed with genuine gaps in understanding regarding weaponization, rather than a deliberate, fully conscious withholding of knowledge.

The "shocking truth" may be that there is no single, simple truth. Heisenberg wasn't a cartoon villain gleefully building a doomsday device, nor was he a Schindler-like figure cleverly thwarting the Nazis from within. He was a human being, albeit one of extraordinary intellect, caught in the gears of history, making choices under immense pressure whose full implications remain debated to this day.

The story of Werner Heisenberg during World War II is not a morality play with a clear hero and villain; it is a tragedy of ambiguity, a stark reminder of the immense ethical responsibilities that accompany scientific genius, especially when entangled with state power and total war. His case forces us to confront uncomfortable questions about the limits of patriotism, the nature of resistance, and the complex, often murky, relationship between knowledge and morality – questions that echo long after the fall of the Third Reich.