Gorbachev's Lost Victory: What if the Soviet Union Never Fell? (Shocking Alternate History)

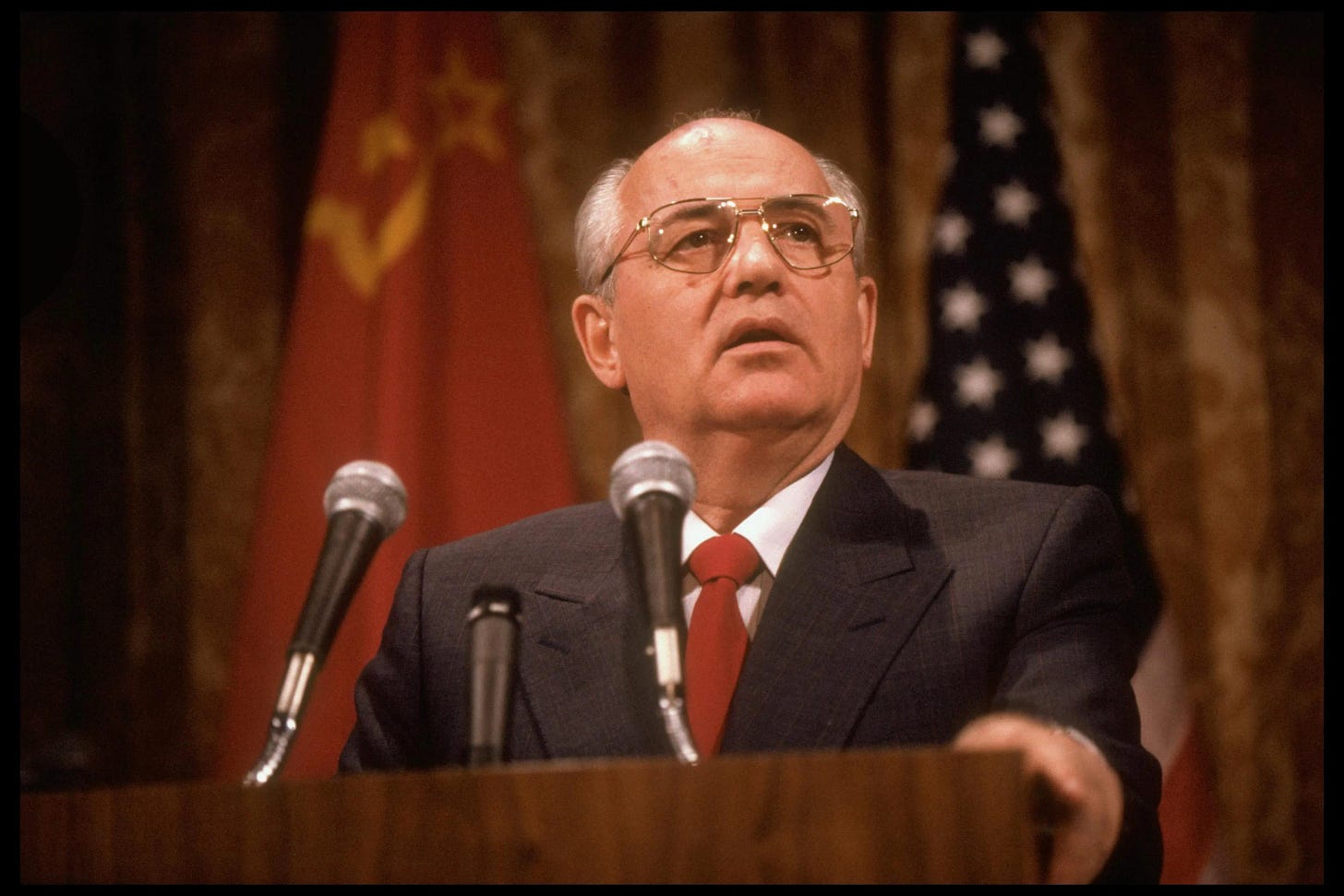

History often feels inevitable in retrospect. The collapse of the Soviet Union in December 1991 is frequently portrayed as the predetermined endpoint of a decaying empire, a final, crumbling surrender to internal contradictions and external pressures. Mikhail Gorbachev, the man presiding over this dissolution, is typically cast as either a tragic hero who unleashed forces he couldn't control or a naive idealist who inadvertently destroyed his own country. But what if this narrative is incomplete? What if hidden within the chaos of *Perestroika* and *Glasnost* was the potential for a different outcome – not collapse, but transformation? What if Gorbachev nearly achieved a *lost victory*?

This exploration delves into a counterfactual history, a timeline branching off from our own, where the USSR, fundamentally reformed yet intact, navigated the turbulent late 20th century and persists into the 21st. It's a shocking alternative precisely because it forces us to question the perceived inevitability of 1991 and consider the profound, cascading consequences of a Soviet Union that *didn't* fall.

The Precipice: Stagnation, Reform, and the Unravelling Thread

To understand how survival might have been possible, we must first acknowledge the desperate state of the USSR by the mid-1980s. The Brezhnev era had bequeathed an economy mired in *stagnation*, technologically lagging behind the West, and burdened by colossal military spending, including the disastrous war in Afghanistan. The *nomenklatura*, the entrenched party elite, resisted meaningful change, while cynicism permeated society. Chernobyl in 1986 wasn't just an industrial catastrophe; it was a devastating symbol of the system's incompetence and secrecy.

Gorbachev's ascent represented a genuine attempt to break this deadlock. *Perestroika* (economic restructuring) aimed to introduce market mechanisms, decentralize planning, and foster innovation. *Glasnost* (openness) sought to revitalize public life, allow criticism, and create a more transparent relationship between the state and the people. These were bold, necessary initiatives. However, they operated under an immense, perhaps underestimated, strain: the inherent tension between liberalization and maintaining the integrity of a vast, multi-ethnic empire built on centralized control and a unifying, albeit fading, ideology.

Gorbachev's dilemma was profound: how to dismantle the oppressive structures of the past without simultaneously dismantling the state itself. He sought renovation, but risked demolition.

The conventional story holds that *Glasnost* fatally weakened the state by allowing long-suppressed nationalist sentiments, particularly in the Baltic republics, Ukraine, and the Caucasus, to surge into the open. Simultaneously, *Perestroika*'s half-measures disrupted the old command economy without effectively establishing a new one, leading to shortages, inflation, and widespread discontent. It seemed the reforms designed to save the Union were, in fact, accelerating its demise.

The Divergence Point: Navigating the Storm

But was collapse the *only* possible outcome? Alternate history hinges on plausible points of divergence. For the Soviet Union to survive under Gorbachev's reforms, several key developments would need to have unfolded differently:

1. A More Controlled 'Glasnost': Perhaps openness could have been introduced more gradually, or with firmer "red lines" initially. While antithetical to true liberalization, a state still possessing formidable security apparatuses might have attempted to manage the flow of information and dissent more carefully, slowing the pace of nationalist mobilization without entirely crushing it. This is morally problematic, of course, but potentially conceivable within the logic of authoritarian reform.

2. Successful Economic Sequencing: The Chinese model, often cited contrastingly, involved market reforms *preceding* significant political liberalization. What if *Perestroika* had yielded tangible economic benefits *before* *Glasnost* fully took hold? Imagine if early joint ventures thrived, if agricultural reforms boosted food supplies quickly, or if cooperative enterprises successfully filled consumer gaps. This could have generated popular buy-in and tempered secessionist impulses driven by economic despair.

3. The Union Treaty's Success: Gorbachev’s desperate, last-ditch effort was the proposed New Union Treaty, designed to create a decentralized federation of sovereign republics with a common president, foreign policy, and military. In our timeline, the August 1991 hardliner coup destroyed this possibility. But imagine a scenario where the coup never happens, or fails less dramatically, *and* key republics like Ukraine are persuaded (perhaps through greater concessions or under different leadership) to sign on. A looser, federal USSR, granting significant autonomy while preserving a core structure, was Gorbachev's intended "victory."

4. Managing Nationalism Differently: Could Moscow have offered substantial autonomy or asymmetrical federal arrangements *earlier* and more genuinely to republics like Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, potentially placating mainstream nationalist movements while isolating extremists? This would have required a foresight and flexibility the Kremlin historically lacked, but it represents a path away from outright confrontation.

Visualizing such a complex alternate reality can be challenging. The intricacies of political maneuvering, economic shifts, and popular sentiment are difficult to capture purely through text. For a deeper dive into the potential dynamics and visual representation of a surviving Soviet Union, consider this exploration:

Contours of a Reformed Soviet Union

What would this surviving USSR look like today? It certainly wouldn't be the totalitarian monolith of Stalin or the stagnant gerontocracy of Brezhnev. It might resemble something unprecedented:

Political System: Likely a form of *managed democracy* or competitive authoritarianism. The Communist Party might still hold constitutional primacy but allow internal factions, contested elections within limits, and significant power devolved to republican governments under the Union Treaty. Think perhaps a looser, more politically diverse version of modern China, but with a lingering Leninist framework. Human rights and political freedoms would likely be far more constrained than in the West, but potentially greater than under its own past.

Economy: A mixed, state-capitalist system. Large state-owned enterprises dominating strategic sectors (energy, defense) alongside a regulated private sector and continued foreign investment. It might avoid the devastating *shock therapy* and oligarchic plunder that characterized 1990s Russia, leading to potentially less inequality but also persistent inefficiencies and state interference. Its integration into the global economy would be cautious and strategic.

Geopolitics: A continued major pole in a multipolar world. No unchallenged American hegemony in the 1990s. NATO expansion eastward would likely have been halted or significantly curtailed. Conflicts like the Yugoslav Wars might have unfolded differently, with a powerful USSR playing a direct role. Its influence in Central Asia, Eastern Europe (though likely diminished), and parts of the developing world would remain substantial. The "End of History" thesis proposed by Francis Fukuyama would be demonstrably false from the outset.

Society and Culture: *Glasnost*, even if managed, would have irrevocably changed society. Greater access to information (though likely curated), more open social discourse (within limits), and diverse cultural expression would exist alongside state propaganda. National identities within the republics would be strong, possibly leading to ongoing tensions managed through the federal structure, but without the full separation achieved in our timeline.

This alternative USSR wouldn't be a utopia, nor necessarily a benign force. It would be a complex, internally contradictory power, grappling with the legacies of its past while forging a unique path – a *Red Leviathan* reformed, not slain.

Global Ripples and Unforeseen Consequences

The survival of the Soviet Union would have reshaped the entire trajectory of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. The rise of China might have occurred differently, potentially facing a more direct ideological and geopolitical competitor. The trajectory of globalization, the wars in the Middle East, the development of international institutions – all would bear the imprint of a persistent Soviet superpower, albeit one vastly different from its Cold War iteration.

Would this world be "better" or "worse"? It's impossible to say definitively. Perhaps the absence of chaotic collapse would have prevented certain conflicts and forms of instability. Conversely, the persistence of a powerful, semi-authoritarian bloc might have stifled democratic movements elsewhere and led to different, potentially larger-scale confrontations. The fates of millions in Ukraine, Georgia, the Baltic States, and Central Asia would be tied to Moscow in ways fundamentally different from their current independent (though often precarious) status.

Considering this alternate path forces us to appreciate the *contingency* of history. The fall of the Soviet Union was not a simple inevitability written in stone. It was the result of specific choices, crises, and convergences – moments where a different turn, a slightly more successful reform, a less virulent nationalist surge, or a more adept handling of dissent might have led down Gorbachev's path of *reformed survival*. It was, perhaps, a victory within his grasp, lost amidst the very forces he unleashed.

Reflecting on this lost victory compels us not just to reimagine the past, but to critically examine the assumptions we hold about political change, the resilience of empires, and the unpredictable consequences of seeking reform from within leviathan structures. The ghost of the Soviet Union that might have been continues to haunt our understanding of the world that is.