Dresden Reborn: The Untold Story of Rebuilding After the 1945 WW2 Firebombing Horror

The bombing of Dresden in February 1945 remains one of the most controversial and devastating events of World War II. While the historical debate concerning its strategic necessity continues, what is often overlooked is the incredible story of resilience and rebirth that followed. This essay delves into the untold story of Dresden's reconstruction, exploring the physical, social, and psychological challenges faced by its citizens, and highlighting the remarkable efforts to rebuild not just a city, but a collective identity shattered by the flames.

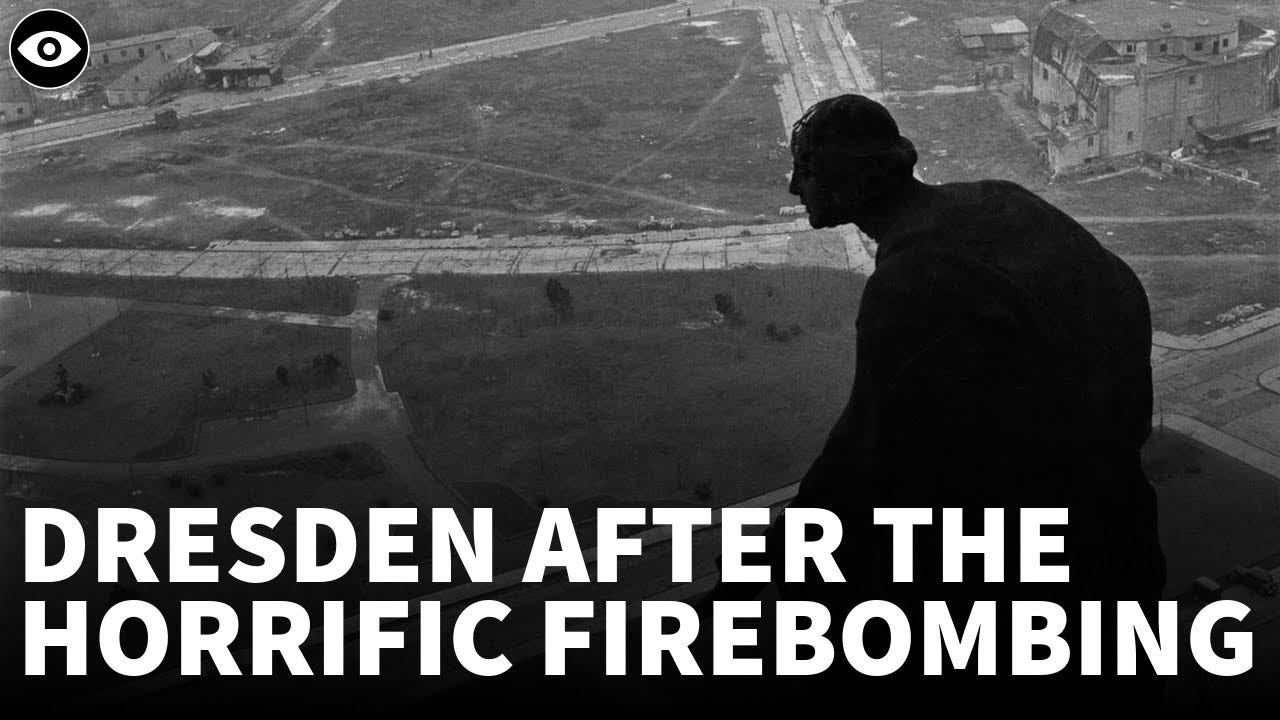

The Inferno and Its Aftermath

On the night of February 13th and 14th, 1945, Allied forces unleashed a series of bombing raids on Dresden, creating a firestorm that consumed much of the city center. Tens of thousands perished in the inferno, and the once-proud baroque architecture of *Elbflorenz* (Florence on the Elbe) was reduced to rubble. The immediate aftermath was a scene of unimaginable devastation. Survivors emerged from basements and shelters to find their homes destroyed, their families lost, and their city unrecognizable. The sheer scale of the destruction presented an overwhelming challenge.

The initial response was focused on survival: searching for loved ones, clearing debris, and burying the dead. The psychological trauma was profound. The experience of witnessing such widespread death and destruction left deep scars on the collective psyche of Dresden's population. Many suffered from post-traumatic stress, anxiety, and depression. The war had not only taken lives and destroyed buildings; it had eroded the very foundation of their existence. The logistical challenges were immense. Food, water, and medical supplies were scarce. The city's infrastructure was crippled, making communication and transportation extremely difficult. Yet, amidst this chaos and despair, the seeds of resilience were sown.

The People's Initiative: Rebuilding from the Rubble

The rebuilding of Dresden was not a top-down, centrally planned process, at least not initially. In the immediate postwar years, the initiative came largely from the people themselves. Driven by a desperate need to survive and a burning desire to reclaim their city, ordinary citizens began the arduous task of clearing the rubble and salvaging what they could. This was a monumental undertaking, requiring immense physical labor and unwavering determination. Women, children, and the elderly all participated, working tirelessly to clear the streets and begin the long process of reconstruction.

The sheer volume of debris was staggering. Millions of cubic meters of rubble needed to be removed, brick by brick. Much of this work was done by hand, using simple tools and sheer manpower. The task was made even more difficult by the presence of unexploded bombs and other dangerous materials. Despite the risks and hardships, the people of Dresden persevered, driven by a deep sense of collective responsibility and a refusal to succumb to despair. This period was marked by a remarkable display of *Volksgeist*, a collective spirit of resilience and determination to rebuild.

"From the ruins rose not only buildings but a renewed sense of community and shared purpose. The people of Dresden, united in their suffering, found strength in each other and worked together to create a new future."

The spirit of *Wiederaufbau* (reconstruction) permeated every aspect of life. Schools were reopened in makeshift classrooms, churches were temporarily repaired, and community centers were established to provide support and assistance to those in need. This grassroots effort was essential in maintaining morale and providing a sense of hope during the darkest of times. The commitment and sacrifice of ordinary citizens laid the foundation for the more formal reconstruction efforts that would follow.

Socialist Reconstruction and the Urban Landscape

As East Germany became a socialist state, the rebuilding of Dresden became intertwined with the political and ideological goals of the regime. The communist government saw the reconstruction as an opportunity to create a new, socialist city, one that reflected their vision of a classless society. This involved both preserving certain historical landmarks and constructing new buildings in the socialist style. The *Kulturpalast* (Palace of Culture), built in the 1960s, is a prime example of socialist architecture in Dresden.

The government prioritized the construction of housing, schools, and factories, aiming to improve the living conditions of the working class. However, the focus on functionalism often came at the expense of aesthetics and historical preservation. Many of Dresden's pre-war buildings were deemed too bourgeois or decadent to be preserved, and were replaced with modern, often drab, concrete structures. This led to tensions between those who wanted to preserve the city's historical character and those who embraced the socialist vision of a new urban landscape.

Despite the ideological constraints, significant efforts were made to restore some of Dresden's most iconic landmarks. The Zwinger Palace, a masterpiece of baroque architecture, was painstakingly rebuilt, as was the Semper Opera House. These projects were seen as symbols of the city's cultural heritage and were prioritized by the government. However, the reconstruction process was slow and often fraught with challenges, including shortages of materials and skilled labor. The Frauenkirche, however, remained a bombed-out ruin, a poignant symbol of the war's devastation and a painful reminder of the past.

The Frauenkirche: A Symbol of Reconciliation

The fate of the Frauenkirche, or Church of Our Lady, encapsulates the complexities of Dresden's reconstruction. Left in ruins after the bombing, it stood for decades as a silent witness to the horrors of war and the division of Germany. During the East German era, the church was deliberately left unrestored as a reminder of the Allied bombing. However, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, a movement began to rebuild the Frauenkirche as a symbol of reconciliation and hope.

The reconstruction project was a monumental undertaking, requiring years of planning, fundraising, and skilled craftsmanship. Thousands of fragments of the original church were painstakingly cataloged and reincorporated into the new structure. The use of both original and new materials created a visually striking contrast, highlighting both the destruction of the past and the hope for the future. The rebuilding of the Frauenkirche became an international effort, with donations coming from around the world.

The rebuilt Frauenkirche was consecrated in 2005, sixty years after the bombing. The event was a powerful symbol of healing and reconciliation, attended by dignitaries from around the world. The church has since become a major tourist attraction and a symbol of Dresden's rebirth. Its restoration serves as a testament to the enduring power of human resilience and the ability to overcome even the most devastating of events. The golden cross on top of the dome, a gift from Britain, serves as a poignant reminder of the wartime animosity and the subsequent healing.

Dresden Today: A City Reclaimed

Today, Dresden is a vibrant and thriving city, a testament to the remarkable resilience of its people. The city's historical center has been largely restored to its former glory, with its baroque architecture and cultural landmarks attracting visitors from around the world. However, the scars of the war are still visible, a reminder of the city's tragic past.

The city has successfully blended its historical heritage with modern development, creating a dynamic and forward-looking environment. Dresden is now a major center for technology, research, and education, attracting a young and diverse population. The city's cultural scene is thriving, with world-class museums, theaters, and music venues. The *legacy of Wiederaufbau* continues to inspire the people of Dresden, fostering a sense of community and shared purpose. The reconstruction has also spurred important conversations about memory, history, and the ethics of war.

The rebuilding of Dresden is more than just a story of physical reconstruction; it is a story of social, psychological, and cultural renewal. It is a story of a city that was brought to its knees but refused to be defeated. It is a story of the enduring power of the human spirit to overcome even the most unimaginable of tragedies. The lessons learned from Dresden's experience are relevant not only to other cities that have suffered from war and disaster but also to all of humanity.

The narrative of Dresden’s rebirth is a complex one, filled with both triumphs and compromises. From the immediate post-war citizen initiatives to the politically charged reconstruction efforts under socialist rule, and finally to the reunified Germany’s commitment to restoring the Frauenkirche, the city’s journey embodies the enduring human capacity for resilience and reconciliation. It serves as a profound reminder that even in the face of unimaginable devastation, hope and renewal can prevail.

Dresden's story is not just about bricks and mortar; it's about the human spirit's unwavering capacity for hope and renewal in the face of unimaginable devastation. It serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of memory, reconciliation, and the enduring quest for peace.

The reconstruction of Dresden serves as a powerful testament to the human capacity for resilience and the transformative power of reconciliation. The city's journey from ashes to renewed glory offers a beacon of hope for communities worldwide facing the daunting task of rebuilding after conflict and disaster.

Dresden's legacy is a potent reminder that even the most devastating events can be overcome with determination, collaboration, and a deep commitment to preserving cultural heritage and fostering lasting peace.

The echo of the bombs may still linger, but the resounding chorus of rebirth and reconciliation now defines Dresden, a phoenix risen from the ashes.