Concrete and Conscience

An Anatomy of the Berlin Wall

The image above captures the precise nanosecond where history fractured. We begin our investigation at the end of the narrative because to understand the Wall, one must understand its failure. Here, at the twilight of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), we witness a tableau that would have been a capital offense only hours prior.

The photograph presents a study in contrasting textures and psychologies: on the right, the rigid, field-grey uniformity of the Nationale Volksarmee (NVA); on the left, the chaotic, colorful, denim-clad assertiveness of the West Berlin populace. The border guard, traditionally an avatar of state-sanctioned violence and the face of the ‘Anti-Fascist Protection Rampart,’ stands with his hands clasped behind his back—a posture of disciplined restraint, yet his facial expression betrays a profound bewilderment. He is a young man, likely a conscript, whose entire training regarding the ‘imperialist enemy’ is disintegrating in real-time.

The extended hand of the civilian is the focal point of this historical rupture. It is not merely a greeting; it is a test of reality. For twenty-eight years, the space between these two men was the ‘Death Strip,’ a zone defined by landmines, tripwires, and the standing Befehl 101—the order to shoot. By reaching across the barrier, the civilian is physically dismantling the geopolitical abstraction of the Cold War. The guard’s refusal to engage tactically, his shift from combatant to spectator, signifies the collapse of the state’s monopoly on force. This moment encapsulates the ‘Friedliche Revolution’ (Peaceful Revolution). It was not artillery that brought down the concrete, but the sheer, overwhelming pressure of human presence and the sudden, collective realization that the emperor had no clothes. The psychological depth here is staggering; the guard is realizing he is no longer the warden of a prison nation, but a witness to its liberation.

The Kinetic Frenzy of Separation: August 1961

If the first image represents the exhale of history, this second artifact represents the sharp, terrified intake of breath. We rewind to the genesis of the trauma: August 15, 1961. The subject is Conrad Schumann, a 19-year-old Bereitschaftspolizist, and his action is the single most recognizable icon of the Cold War’s inception. Unlike the static resignation of the 1989 guard, Schumann is pure kinetic energy. The photograph, captured by Peter Leibing at the corner of Ruppiner Straße and Bernauer Straße, freezes the exact moment of decision. The barrier is not yet the imposing concrete slab of later years; it is a hastily deployed coil of concertina wire, a fragile delineation that still allowed for the possibility of escape.

Schumann’s leap is a masterclass in the psychology of risk. Note the discarded PPSh-41 submachine gun falling away from his body; he is shedding his identity as an enforcer of the state to reclaim his agency as an individual. The blurred motion suggests the desperation of the act. At this juncture, the border was porous but rapidly hardening. Schumann stood for hours, smoking nervously, heckled by West Berliners shouting ‘Komm rüber!’ (Come over!), while his superiors were distracted. His jump is not just a physical vault; it is a metaphysical transition from the Collective East to the Liberal West. This image serves as the ultimate counter-narrative to the GDR’s propaganda. If the socialist paradise were truly a protection against fascism, its own guardians would not risk death to flee it. Schumann’s suspended form hangs over the wire as an eternal question mark against the legitimacy of the Ulbricht regime, proving that from day one, the Wall was a prison, not a fortress.

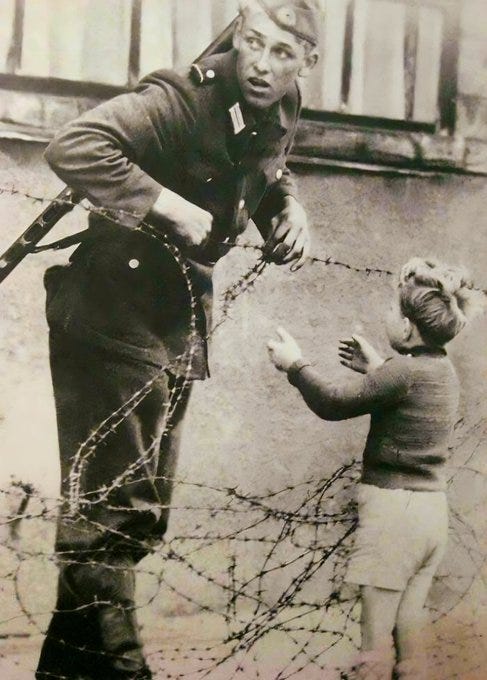

The Ambiguity of Duty: A Moment of illicit Mercy

Between the kinetic escape of Schumann and the passive surrender of 1989 lies the murky, grey reality of daily existence along the sector boundary. This third image provides a rare, almost forbidden glimpse into the cognitive dissonance experienced by those in uniform. The photograph shows an East German guard lifting the barbed wire to allow a young boy to pass. The body language of the soldier is forensic in its storytelling: his eyes are not on the child, but darting nervously over his left shoulder, scanning for his commanding officer or a Stasi informant. He is committing an act of treason to perform an act of humanity.

This interaction deconstructs the monolithic view of the ‘Grepos’ (border police) as unthinking automatons. It reveals the terrifying moral calculus required to survive in a totalitarian system. The soldier knows that compassion is a weakness the state will punish. The composition of the photo—the sharp, menacing tangles of the wire contrasted against the soft vulnerability of the child—highlights the absurdity of the partition. This was likely taken in the very early days of the erection of the Wall, before the installation of the ‘death strip’ infrastructure made such intimate encounters impossible. It captures the transition period where the organic connections of a city—families, neighbors, school runs—were being violently severed by inorganic politics. This soldier, caught in the act of mercy, represents the ‘banality of goodness,’ a fleeting resistance against the encroaching brutalism that would soon define the Berlin border for three decades.