Beyond the Wicker Chair: Unraveling Škoda's Unexpected Use of Cane in Automotive History

When we think of Škoda today, we often conjure images of practical, reliable, and cleverly designed vehicles – a stalwart brand within the Volkswagen Group known for offering exceptional value. Its modern identity is built on solid engineering and thoughtful features, hallmarks of contemporary automotive mass production. Yet, lurking beneath this familiar surface lies a rich, complex, and often surprising history, deeply intertwined with the turbulent currents of 20th-century Europe. One of the most intriguing and lesser-known aspects of this past involves the use of a material far removed from the steel, plastic, and aluminum that dominate car manufacturing today: cane.

The idea of incorporating woven cane, typically associated with furniture or baskets, into the structure or finishing of an automobile might seem quaint, perhaps even frivolous. Was it merely an aesthetic flourish, a fleeting design trend? The reality, as is often the case with industrial history forged under duress, is far more complex and revealing. Škoda's use of cane wasn't primarily about style; it was a testament to resourcefulness, necessity, and engineering ingenuity born from specific historical and economic circumstances.

Setting the Stage: From Laurin & Klement to Post-War Realities

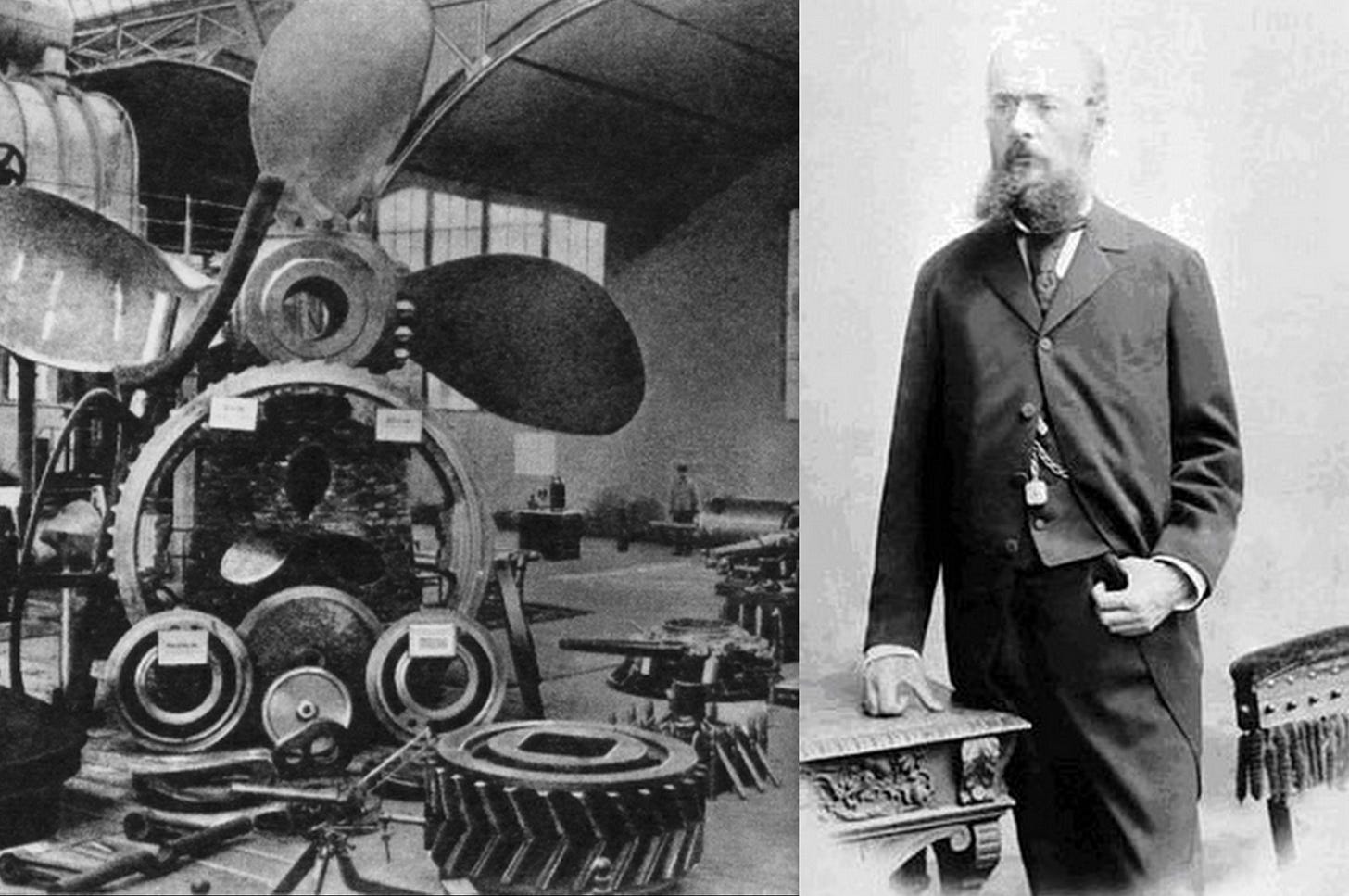

To understand why Škoda turned to unconventional materials, we must first appreciate its origins and the environment in which it operated. Founded initially as Laurin & Klement in 1895 in Mladá Boleslav (then part of Austria-Hungary, later Czechoslovakia), the company quickly established a reputation for quality bicycles, motorcycles, and eventually, automobiles. Its merger with the industrial conglomerate Škoda Works in 1925 solidified its position as a major force in Central European automotive manufacturing.

However, the devastation of World War II and the subsequent political realignment of Europe dramatically altered the landscape. Czechoslovakia found itself within the Soviet sphere of influence, adopting a centrally planned economy. This system brought profound challenges for industries like automotive manufacturing. Resources were often scarce, supply chains were dictated by state planning rather than market demand, and access to Western technologies and materials was severely restricted. Reconstruction efforts prioritized heavy industry and infrastructure, often leaving consumer goods manufacturers, including car makers, to make do with limited allocations.

The post-war era, particularly the late 1940s and 1950s, was a period defined by constraint. For engineers and designers in Czechoslovakia, innovation often meant finding clever ways to circumvent limitations rather than pursuing boundary-pushing technology reliant on readily available, high-spec materials.

The Cane Connection: More Than Just Decoration

It was within this context of shortage and constraint that cane emerged as a viable material for certain automotive applications in specific Škoda models, most notably variants of the Škoda 1101/1102 "Tudor" and its successor, the Škoda 1200/1201 series, particularly the practical station wagon (STW) versions produced in the 1950s and early 1960s.

Where was cane used? Photographic evidence and historical accounts show its application primarily in interior components. This could include side panels, luggage compartment separators, or potentially even sections of seating or door cards in some utility or "woody" style variants. It wasn't typically used for primary structural elements, but rather for panels, partitions, and finishing touches where its properties offered a pragmatic solution.

Why cane? Cane, derived from the outer layer of the rattan plant, possesses several useful characteristics:

It is lightweight, which is always a consideration in vehicle design.

It is surprisingly strong and flexible for its weight, capable of being woven into durable panels.

It was a natural, relatively abundant, and locally processable material, potentially easier and cheaper to source or import under the planned economy than sheet steel, aluminum, or early plastics, which were often prioritized for strategic industries.

Working with cane drew upon existing craft traditions (like basket weaving or furniture making), potentially utilizing available skills and simpler manufacturing techniques compared to complex metal stamping or plastic molding.

This wasn't about luxury or bespoke coachbuilding in the traditional sense. It was about fulfilling a functional requirement – creating interior partitions, panels, or surfaces – using the most practical means available under significant economic and material limitations.

To get a visual sense of Škoda's fascinating journey and the kind of vehicles that emerged from this era, exploring historical footage can be incredibly insightful. The ingenuity required to keep production lines moving under such conditions is truly remarkable. For a deeper dive into some of Škoda's unique historical moments, consider exploring resources like this:

The "Real" Reason: Necessity as the Mother of Invention

Therefore, the "real reason" Škoda incorporated cane wasn't a stylistic whim but a pragmatic response to the pressures of post-war reconstruction and the realities of a centrally planned economy. Steel was needed for rebuilding infrastructure, tanks, and heavy machinery. Advanced plastics were nascent and often imported. Aluminum was expensive and strategic. Wood was available, but quality timber suitable for automotive use also had competing demands.

Cane offered a workable alternative for non-critical components. It allowed Škoda to produce vehicles, particularly utilitarian models like station wagons needed for tradespeople and state services, when other materials were simply unavailable or prohibitively expensive. It represents a fascinating case study in material substitution driven by economic necessity.

This use of cane should be viewed not as a compromise in quality, but as an act of profound engineering resourcefulness – adapting design and manufacturing processes to the constraints of the environment, ensuring that mobility could still be provided even when ideal resources were out of reach.

This period contrasts sharply with, for example, the use of wood in American "Woodie" wagons of the same era. While initially born from structural necessity in early car bodies, the American Woodie of the late 1940s and 50s often retained wood (or simulated wood) largely for stylistic reasons, evoking a sense of luxury, nostalgia, and connection to nature. Škoda's use of cane appears far more rooted in immediate, practical problem-solving.

Legacy and Reflection: Echoes of Ingenuity

As Czechoslovakia's economy gradually stabilized and material science advanced, the use of cane in Škoda vehicles faded. Steel, plastics, and composites became the standard, aligning Škoda with global automotive manufacturing trends. Yet, this brief, unconventional chapter remains significant.

It speaks volumes about the resilience and adaptability embedded in Škoda's DNA. The challenges faced during the mid-20th century undoubtedly shaped a culture of finding clever solutions to practical problems – a spirit that arguably echoes today in Škoda's brand philosophy of "Simply Clever." While modern features like ice scrapers in fuel caps or integrated umbrellas are far removed from using woven cane panels, they share a common ancestry: a focus on pragmatic ingenuity driven by understanding user needs and available possibilities.

Looking back at Škoda's use of cane reminds us that the history of technology and industry is rarely a simple, linear progression towards ever-more-advanced materials. It is often a story of adaptation, compromise, and flashes of brilliance sparked by constraint. It forces us to look beyond the surface aesthetics and appreciate the deeper economic, political, and engineering narratives woven into the very fabric – sometimes literally – of the objects we create.

Škoda's surprising history with cane is more than an automotive footnote; it is a compelling reminder that innovation often flourishes most vibrantly not in abundance, but in the face of limitation, compelling us to rethink our assumptions about progress and design.